Few places to shelter

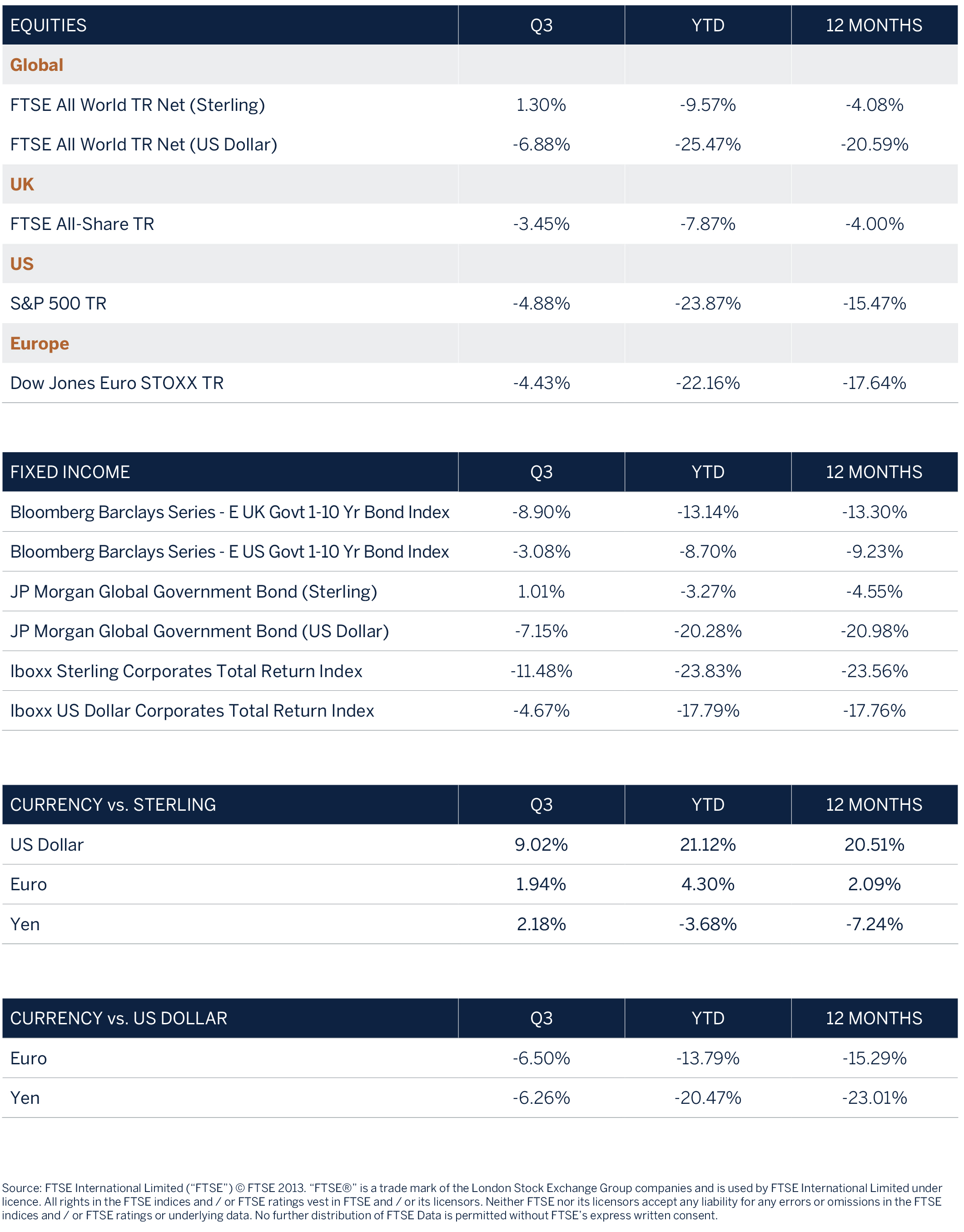

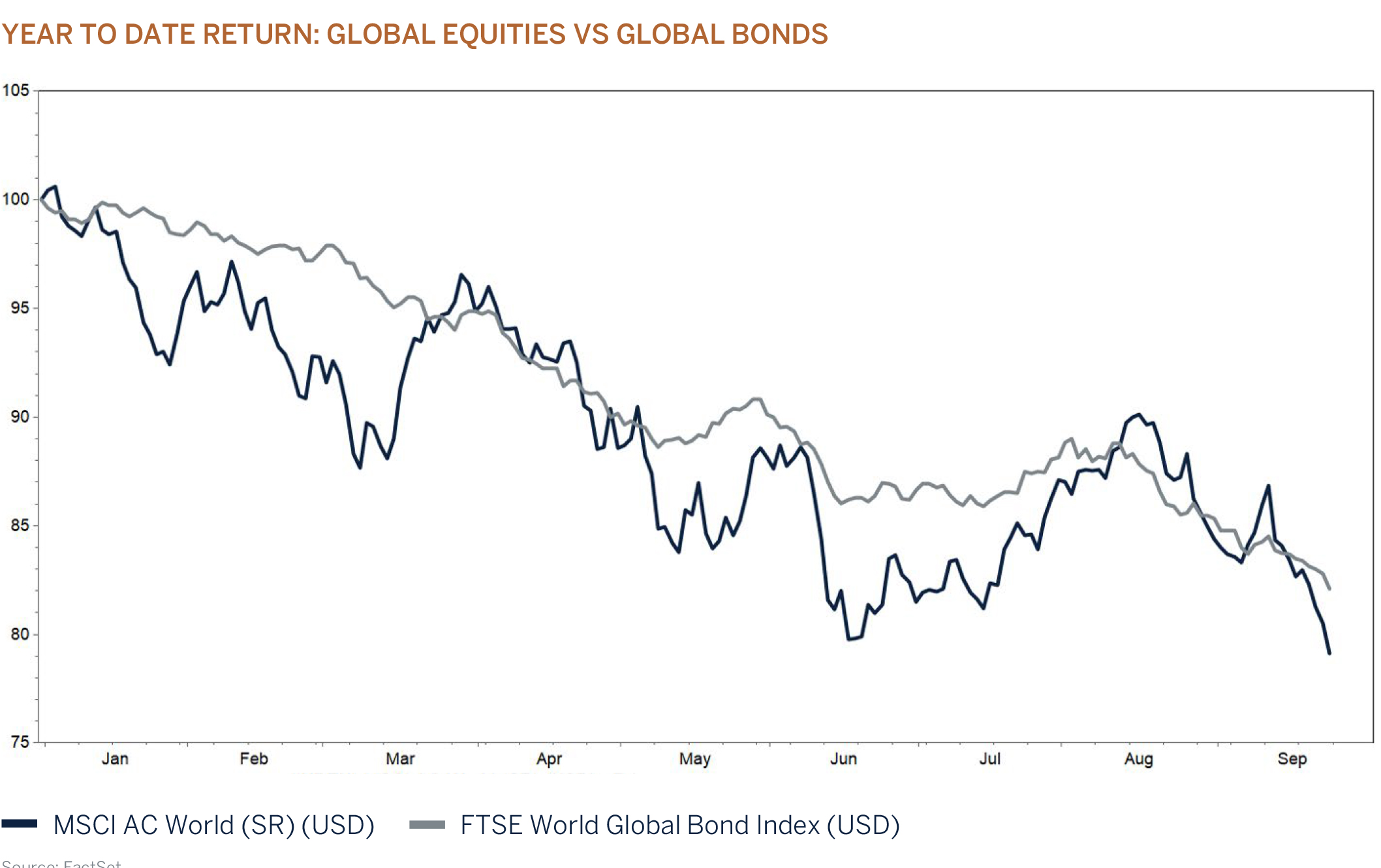

Liquidity is the lifeline for global economies and investment markets. Aggressive monetary easing from global central banks alongside unprecedented fiscal expansion played an important role in stimulating economic growth since the onset of COVID-19 and post the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. But this liquidity combined with consumer pentup demand, supply chain bottlenecks, rapidly increasing energy and food prices (linked to the ongoing war in Ukraine) and tight labour markets have coincided to release the inflation genie for the first time since the early 1980’s. Central banks have recently made their intentions clear and will do “whatever it takes” to bring inflation under control and regain credibility by implementing synchronised hikes in interest rates (monetary tightening) to slow demand. Investors have reacted to this reality and are positioning themselves for the increased risk that central banks, who correctly deem inflation to be more of a long-term evil than a short-term detraction, will cause a widespread economic contraction by hiking interest rates too aggressively. Outside of the US Dollar, which has appreciated by some 17% on a general value basis, there have been few places to shelter this year with both global equity and bond markets down significantly, having reached new lows at the end of the third quarter.

Dealing with the inflation dilemma

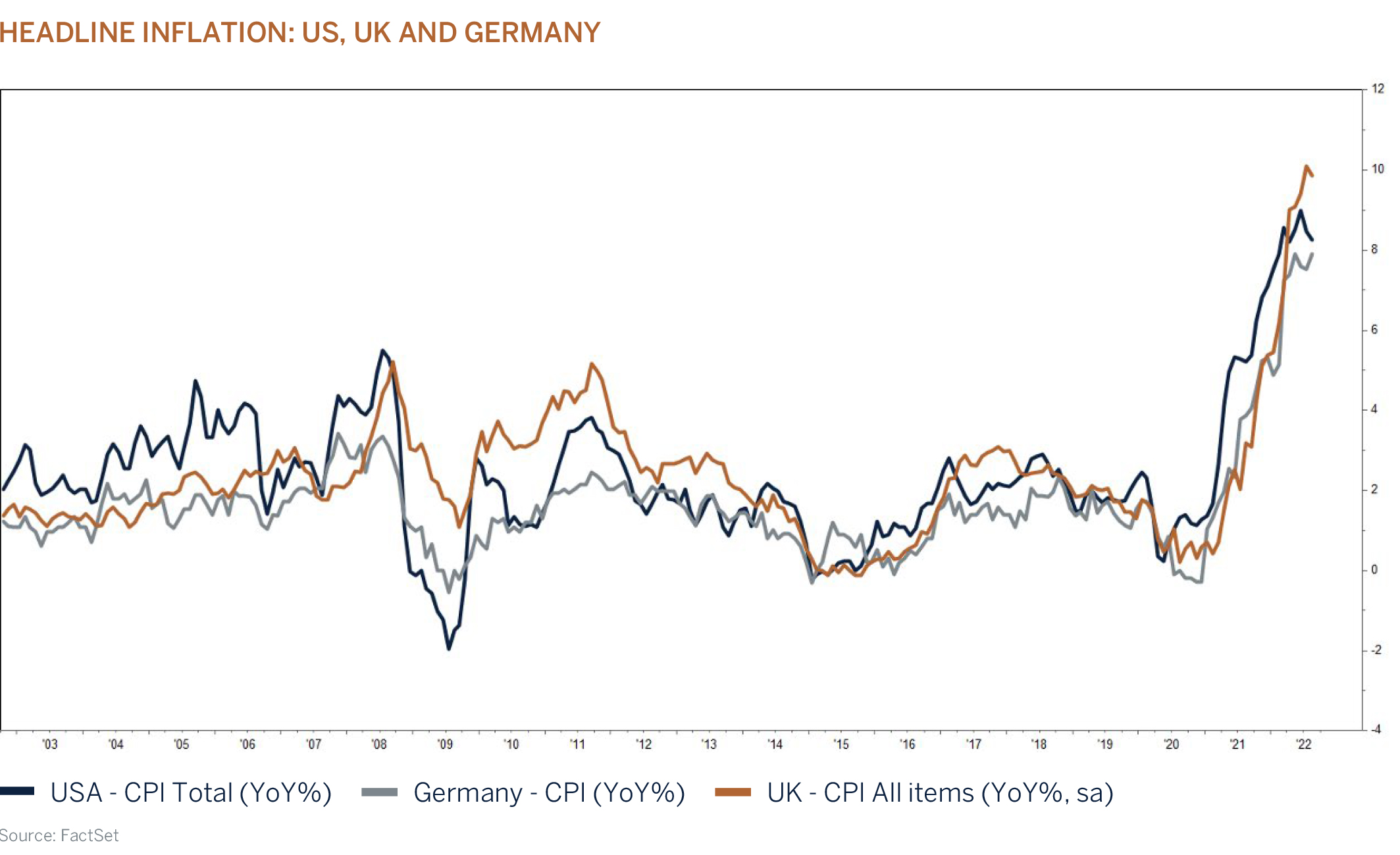

The prospect of high (or above central bank target level) inflation has had many false dawns over recent years but has been kept in check by global trends, such as, the price competition side-effects of globalisation and productivity led technology efficiencies. Numerous warnings about the perils of ‘letting the inflation genie out of the bottle’ due to excessive liquidity/monetary supply (think historically low interest rates and quantitative easing), remained unfounded, until now that is. Perhaps the inflationary storm was already circling before COVID-19, but the actions by central banks to safeguard economies throughout the pandemic certainly threw fuel on the fire. Cautions about rampant money supply exceeding GDP by almost unimaginable multiples went largely unheard as markets continued to dismiss inflation fears as something resigned to the 1980’s. Of course, not all blame can be imparted on central banks, if they hadn’t acted so forcefully and generously the public uproar would have been unprecedented and global growth would have struggled to rebound from the confines of lockdowns. Other factors played their part in creating the perfect storm for inflation to return with a vengeance. Firstly, lockdowns in Asian export economies, especially China, severely impacted global supply chains. Whilst in Europe BREXIT has also hampered supply chains and increased costs at a time when there was significant appetite to spend, and the centuries old ‘supply versus demand’ equation went full tilt. Secondly, Europe’s dependence on Russian energy supplies quickly became a serious issue in the wake of the war in Ukraine. In conclusion, a multitude of factors combined to create the current inflationary headache and easing the pain will not be without its challenges.

Global central banks are now faced with an unenviable balancing act of rapidly withdrawing liquidity whilst imparting the least amount of economic damage, an extremely challenging process with a questionable past. Virtually all have made it very clear that lowering inflation is ‘priority no.1’ and if the price to pay is slower growth or a recession, so be it. Global interest rates are rising quickly and ‘hawkishness’ only seems to be intensifying as each central bank meeting passes. Tighter monetary policy has scant effect on supply chain issues or Putin, but it can combine with the ‘pinch’ of higher inflation to lower demand, thereby interrupting the cycle. The only issue here is that it remains unknown by how much demand will have to be destroyed before inflation slips. Will central banks over-tighten monetary policy, engineering a lasting bout of stagflation? Currently, whilst there are signs of annualised headline (inc. food and energy) inflation easing, core inflation is exhibiting no signs of abating as services remain strong. As long as this persists, central banks will continue to spout hawkish rhetoric in an effort to rein in consumer spending.

Only time will tell if there is a favourable outcome to this inflationary saga. It is clear that global bond markets continue to price-in even higher interest rates and are currently turning a blind eye to the economically damaging after-effects. To be clear, we do not believe interest rates are returning to the lofty levels of the 1980’s but there is still more to go. Until inflation readings begin to exhibit evidence of a sustained turnaround, central banks have little choice but to remain hostile after many years of over generosity. Some of this hostility is likely to come in the form of ‘verbal’ communications warning of higher terminal rates that in fact may or may not come to fruition. We remain optimistic that a combination of restrictive monetary policy, the negative feedback loop of higher inflation itself (reduction in affordability) and rolling base effects will have ‘an effect’ in the coming months. Is inflation on a rapid path back to central bank target levels (circa 2%)? We think not but history has taught us that markets will undoubtedly breathe a sigh of relief when we are out of the eye of the storm and inflation numbers are again simply heading lower, something we expect to see within the next 3-6 months.

UK - The ‘big’ after-effects of the ‘mini’ budget

Recently appointed UK Prime Minister Liz Truss’s government took markets by surprise last week, unveiling the most radical package of tax cuts in 50 years. Cited by the Chancellor as ‘a new approach for a new era’, the fiscal package is designed to lift the UK economy out of a decade of weakness and return it to a target of +2.5% trend growth. Ambitious indeed but so were the measures which included cutting the basic rate from 20% to 19% and abandoning next year’s proposed hike in corporation tax. These generous measures, amongst others, come at an estimated cost to the UK of £161 billion over the next five years which is not positive for an economy with an already sizeable debt burden which is now set to reach its third-highest peak since WW2. It is worth noting that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) quickly urged the UK government to ‘re-evaluate’ the package of unfunded tax cuts, citing the inequality and inflationary ramifications.

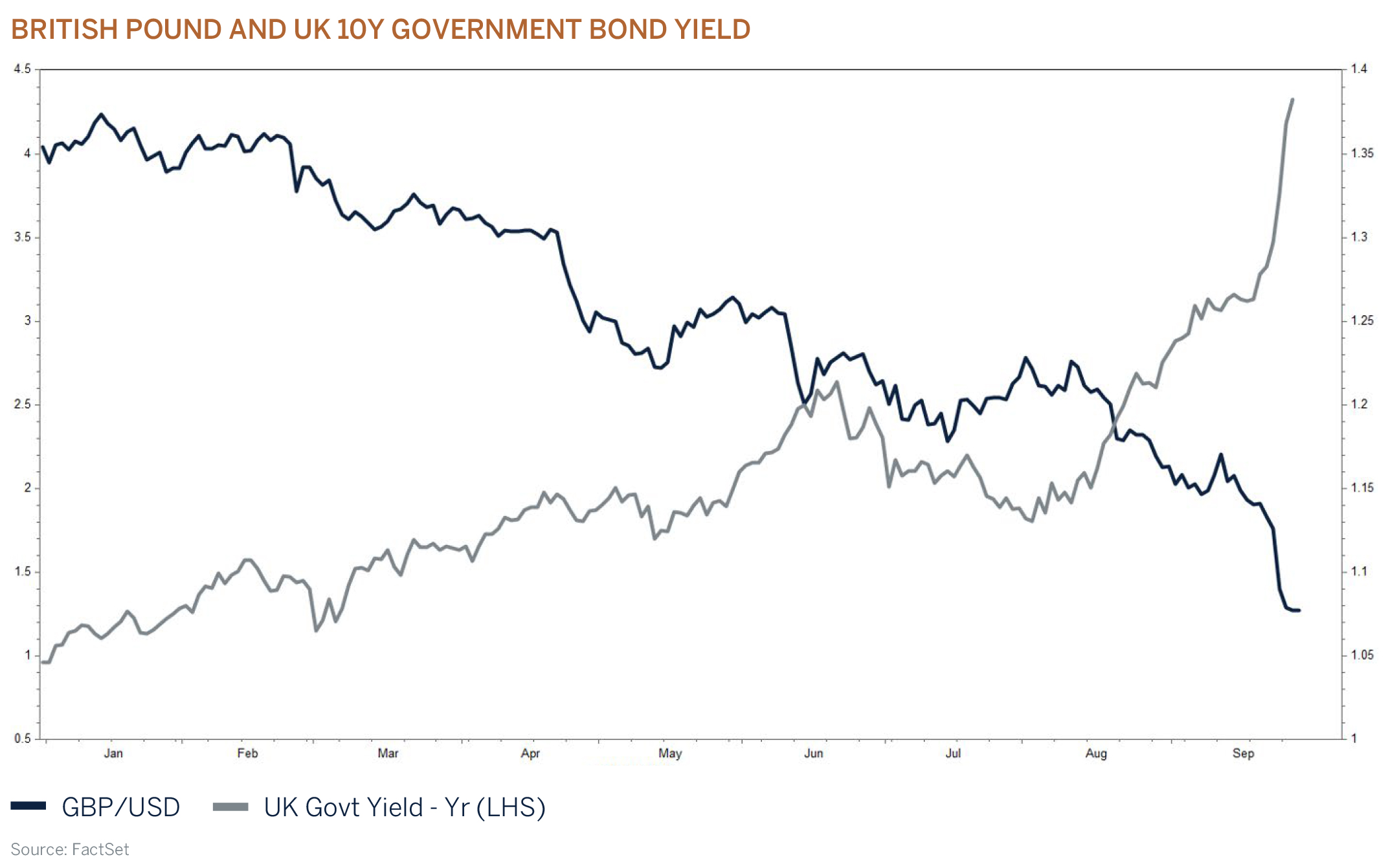

However, rising debt to GDP levels have to take a back seat for now as they are not the primary reason for such a marked negative reaction in both UK government bonds and Sterling (see chart below). The UK economy is battling inflation close to a 40-year high, currently nearly five times the central bank’s target and the Bank of England are stepping up efforts to dampen demand (thereby lowering inflation) the only way they can in the current environment by raising interest rates. Therein lies the catalyst behind the recent volatility – a vicious cycle has been created between the government and central bank. The government’s fiscal largesse will exacerbate the very ‘inflationary’ demand the central bank are trying to tame with the net outcome being a sharp readjustment higher in the outlook for interest rates. Earlier expectations that interest rates could peak in the 3% to 3.5% range have been quickly revised higher with some analysts now forecasting a number starting with at least a 5% or even 6% handle. These fears do not go unfounded as the Bank of England have been quick to warn of a ‘significant monetary policy response’, further spooking government bond yields. The 10-year benchmark yield has more than doubled since mid-August and is now higher by an eye-watering (circa) 430 basis points from its low in 2020.

Somewhat contradictory to conventional wisdom, this (potentially) higher growth outlook and upwardly revised interest rate outlook has also resulted in Sterling depreciating sharply. In the days ahead of the government’s announcement, Sterling had already breached it’s all time low against the US Dollar (1-16 in 1984), therefore, was particularly vulnerable to any negative new-flows. The volatility that ensued after the mini budget pushed the currency pair to a low of 1.035 but has since retraced some of these losses. With the Euro having already fallen through ‘parity’ with the US Dollar, attention quickly turned to the prospect of Sterling suffering the same fate. Time will tell if this comes to fruition, if it does then the UK’s inflation problem will only get worse.

In summary, UK bonds and Sterling will remain volatile until markets can ascribe success or failure to the government’s stimulus plans and that will take some time. We remain underweight fixed income as an asset class throughout multiasset portfolios which continues to add to relative performance. However, we are mindful that sharply higher yields, both in the UK and globally, should begin to represent value once some light at the end of the ‘monetary tightening cycle’ becomes visible.

Conclusion

The scale of the recent sell-off indicates that a recession is increasingly being priced in, but investors should expect the current bout of volatility to continue until inflation is seen to be moderating. Fiscal stimulus may assist households and companies to deal with worryingly higher energy prices in the short term, but the associated increase in interest rates that are sure to follow may turn out to be more costly as the world economy enters the next cyclical downturn.

The correction in investment markets is starting to provide opportunities for patient investors. Bond yields are back to the levels last experienced in 2008 and are offering attractive long-term inflation adjusted returns and equity market valuations are starting to discount a worse than expected outlook for company profits over the next year. In addition, investors have already adjusted their equity and cash allocations to 2020 levels, i.e. positioning for the worst. An improvement in the outlook for inflation is sure to provide an underpin to risk assets from the current levels and could result in investment markets reaching the next inflection point as we move from the current phase of “despair” to “hope” - a period which has historically generated the greatest returns for equity investors and over a relatively short period of time. And, while the world economy is entering a more challenging period and geopolitical risks remain heightened, it is important to note the strength of corporate, financial sector and household balance sheets during this cycle, which will help to weather the storm.

As we navigate through these trying times, we will continue to invest in quality companies with strong balance sheets and structural growth drivers that are less sensitive to the economic cycle. From an asset allocation perspective, we remain neutral equity and overweight cash and will be looking to deploy capital into fixed income assets, where we remain underweight, as interest rates move closer to their peak during this cycle.

Investment performance

On an absolute basis it has been another very difficult period for investors although Sterling-based portfolios have held up more favourably due to the weakness of the currency. Our move to a neutral allocation to risk assets (equities) in July added some relative value for the period as did our ongoing underweight positioning to fixed income. There was little respite for our sector allocation (no energy) but our style bias did work for us as investors started to allocate to quality growth companies that have long term competitive advantages and pricing power. Year to date, quality growth has underperformed by some margin but as the economic backdrop continues to battle with headwinds, we expect a rotation back to these types of businesses as investors seek more certainty of returns.

Asset Classes

| Equities | Neutral |

| Fixed Income | Underweight |

| Cash Plus | Overweight |

Asset Allocation

The very strong US Dollar and rapidly increasing interest rates have resulted in cyclical and long dated growth assets, such as information technology, emerging markets and mining shares experiencing the brunt of the pain during the third quarter of 2022. Europe also remains one of the worst performing equity markets this year, given the challenges associated with the war in Ukraine. Gas and oil supply into the region remains a risk and the significant increase in the cost of energy will be a substantial headwind to household balance sheets and company profit margins. However, fiscal support measures (lower taxes and energy subsidies) introduced by governments to combat the higher cost of living and doing business will alleviate some of the near-term pain, while at the same time drive sustainable long-term growth through investment initiatives such as the renewed focus on expanding renewable energy generation capacity. The question of course is, will these fiscal stimulus measures announced in countries such as the UK result in even stickier inflation which will most likely be accompanied by even higher interest rates and an increased risk of a recession down the line? In our opinion increased central bank policy error risks continue to translate into a need for balance in portfolios, and why we think a more neutral allocation to risk assets and government bonds currently makes sense.

Global equity – Neutral

| Consumer Discretionary | Overweight |

| Consumer Staples | Neutral |

| Energy | Underweight |

| Financials | Neutral |

| Healthcare | Overweight |

| Industrials | Neutral |

| Information Technology | Neutral |

| Materials | Neutral |

| Communications Services | Overweight |

| Utilities | Neutral |

| Real Estate | Underweight |

After a strong start to the third quarter, global equity markets sold off aggressively as the outlook for interest rates became increasingly hawkish and as geopolitical risks in Europe increased. Policy error (monetary, fiscal and political) has perhaps become the largest risk for investors, with recent examples including the “leaking” of the Nord Stream gas pipeline and fiscal developments in the UK. Higher interest rates impact equity valuations in two ways. The first being its impact on valuations as the discount rate adjusts higher and the second, what the change in interest rates means for global growth. A slowdown in global growth tends to tighten financial conditions and result in higher volatility as the outcome for company earnings becomes less certain. In addition, a worsening global economic backdrop affects the likelihood of shocks as well as the vulnerability to negative spillovers and explains why risk assets have sold off so extensively this year.

We do not expect volatility to ease much in the near term. Earnings revisions have turned negative, and the full impact of higher interest rates will only be felt next year. Equity markets are forward looking and have already adjusted, while positioning by asset managers has turned decisively negative with cash and equity holdings back to 2020’s pandemic crisis levels, i.e. a lot of bad news has already been discounted. Investors will do well to focus on the long-term fundamental drivers of companies and not be influenced by the daily vagaries of the stock market. We view risk as the permanent loss of capital, not volatility. Over the long term, share prices do revert to their intrinsic value and at current valuations many shares are once again offering good value – be greedy when everyone else is fearful. While we cannot profess to know exactly when equity markets will turn, history has proven time and time again that the initial phase of a cyclical recovery generates the highest returns for investors, and to try and “time the market” from the current depressed levels can be both risky and expensive. We prefer to hold our nerve and exercise patience during periods of extreme volatility. At Melville Douglas we believe that our proven investment philosophy of investing in quality businesses with strong balance sheets and secular growth drivers will once again provide the necessary underpin in portfolios and remain neutral the asset class.

Fixed Income – Underweight

| G7 Government | Underweight |

| Investment Grade - Supranational | Overweight |

| Investment Grade - Corporate | Neutral |

| High Yield | Overweight |

The rout in global government bond markets continued unabated in the third quarter with yields rising sharply in reaction to ongoing extreme inflationary pressures and therefore, increasingly ‘hawkish’ central banks. Earlier hopes that weakening economic data would convince central banks to adopt less aggressive tightening cycles had cold water thrown on it in July when the US Federal Reserve committed to ‘do whatever it takes’ to bring inflation back in line. This monetary policy mantra has been quickly adopted on a global scale and interest rate expectations continue to climb despite the clear negative ramifications for future economic growth conditions as lowering inflation has become overwhelmingly more important than achieving a ‘soft landing’. Having become accustomed to the luxury of predictable central bank ‘forward guidance’ and the absence of inflationary pressures for many years, global bond markets are now contending with heightened uncertainty on both fronts and their reaction has been distinctly negative.

US government bonds suffered further losses in the quarter with 10-year yields rising over 80 basis points to 3.83%. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) is battling the highest inflation in nearly forty years and has acknowledged that a slowdown in economic growth conditions and a rise in unemployment are prices worth paying to ease rampant price pressures. Five interest rate hikes have now been sanctioned this year with the last three being 75 basis points moves and the tightening phase is not over yet. At the last Fed meeting, interest rate projections were raised even further and now imply rates reaching 4.4% this year and 4.6% in 2023 before moderating to 3.9% in 2024. This ongoing and rapid withdrawal of liquidity will undoubtedly weigh on the growth outlook in the coming quarters, but the Fed has made it clear that the priority must be to lower inflation before it becomes entrenched which would impart more longer-term economic damage than an economic slowdown or recession. Ultimately, whilst economic conditions remain broadly resilient currently, predominantly the employment market, tightening policy aggressively now should dampen demand and weigh on inflation whilst at the same time building in interest rate armoury for the impending slowdown in growth. It remains a fine balancing act for the Fed who still consider that a ‘hard landing’ can be avoided – the jury remains divided.

The UK government bond market has significantly repriced the outlook for tighter monetary policy leading to a marked shift higher in yields across the curve. Whilst global bond yields have been rising in anticipation of further central bank tightening, the UK market has severely underperformed other major developed markets such as the US and Germany over the quarter. So why has this been the case? Like other central banks, the Bank of England’s (BoE) main objective is to implement measures to bring inflation back under control and towards its long-term target of 2%. The BoE has raised rates seven times in the current cycle with the most recent rise of 50 basis points taking the base rate to 2.25%, although so far this has had little effect on dampening consumer demand in the economy. However, it is not just a story about demand, other factors such as elevated labour costs and high energy prices have driven inflation higher with the headline rate hovering around a 40 year high of 10% in August.

The fragility of the bond market was compounded further following the release of the “new” Conservative government’s “go for growth” mini budget. This unorthodox measure of reduced tax receipts (income) and higher spending (at a time when UK finances are already elevated) caused extreme volatility in the bond market, with the 30-year Gilt experiencing its highest daily price swing on record, leading to BoE intervention. Whilst this action has provided some stability in the market, yields ended the month higher with the 10-year benchmark Gilt rising 1.30% to 4.10% as the market discounts further monetary tightening by the BoE. It is difficult to forecast where the base rates will end the year, but our current thinking is that we should receive a further 150 to 200 basis points of tightening, which will take the base rate to between 3.75% and 4.25%, with further tightening in 2023.

Market Performance / as at 30 September 2022