Delayed effects of higher interest rates start to bite

Financial markets started 2023 on an upbeat tone on the back of some positive developments, but lost momentum as the quarter progressed. China’s reopening, lower energy prices in Europe after an unusually warm winter and evidence that inflation has turned the corner all contributed to a belief that a soft landing in the global economy was achievable, and that may still be the case as confidence levels have improved from their lows.

However, persistently high core inflation fuelled by excess savings and a vibrant jobs market changed the narrative from central banks in February. They guided that a step up in the pace of interest rate increases would ultimately be required to slow demand enough to contain inflation. Asset prices reacted to the renewed risk of a policy error by monetary authorities at a time when the global economy is expected to slow as credit conditions tighten and the full lagged effects from higher interest rates start to take hold.

In recent weeks, worrisome memories of the 2008 global financial crisis were reawakened by runs on three US regional banks and by Credit Suisse’s shotgun marriage to UBS - portfolios have no equity exposure to these banks but in the fixed income weightings of some strategies there is negligible, under 0.2%, indirect exposure to Credit Suisse debt. Fortunately, the Federal Reserve (by guaranteeing deposits and by providing banks with access to loans based on the face value of their bond holdings) was much swifter in intervening to stem contagion than in 2007-2008. The long-term risk of promoting moral hazard was probably worth averting a potential systemic banking crisis. The worst appears to be behind us, although we would not be surprised to see a few more casualties during this shake-out as it takes a long time for the effects of higher interest rates to ripple through the system.

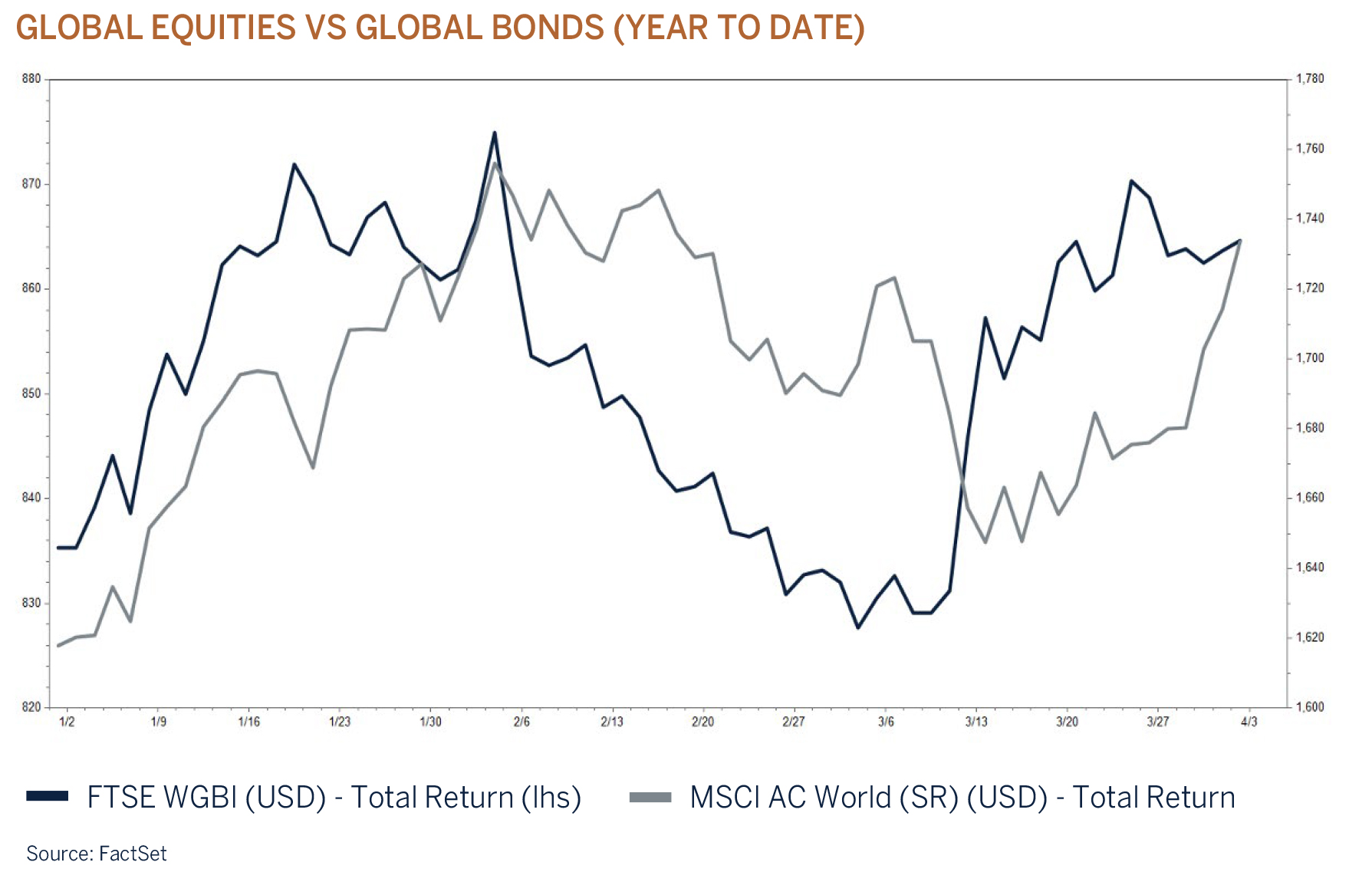

The silver lining is that central banks tempered their hawkishness lest they tip the banking sector into meltdown and the more benign interest rate outlook boosted government bond prices. This acted as a powerful countervailing force for global stock markets during the latter part of March amidst sliding corporate earnings expectations. Financial market expectations are now discounting, prematurely in our view, a series of interest rate cuts in the second half of the year. We believe the path for interest rates will primarily be determined by the outlook for inflation, and with core inflation looking set to remain stubbornly high in the short term, central banks are unlikely to be in a hurry to ease tight monetary conditions by lowering interest rates early. This raises the prospect that markets, in the months ahead, will again adjust lower on renewed fears of central bank policy error. Monetary authorities run the risk of raising rates too high, keeping them there for too long and not easing until it has become clear that inflation is under control, but by then the economic cycle is likely to have already turned for the worse leading to a recession and a natural decline in inflation, as it always does during an economic contraction.

Rising risks of recession

The global economic expansion during the first quarter of 2023 has positively surprised, albeit due to the favourable base effects from last year. China’s reopening, a European rebound from its energy price shock and a steady improvement in the global supply chain (caused by the dislocations associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) have resulted in global GDP growth tracking above its potential despite the sharp increase in interest rates.

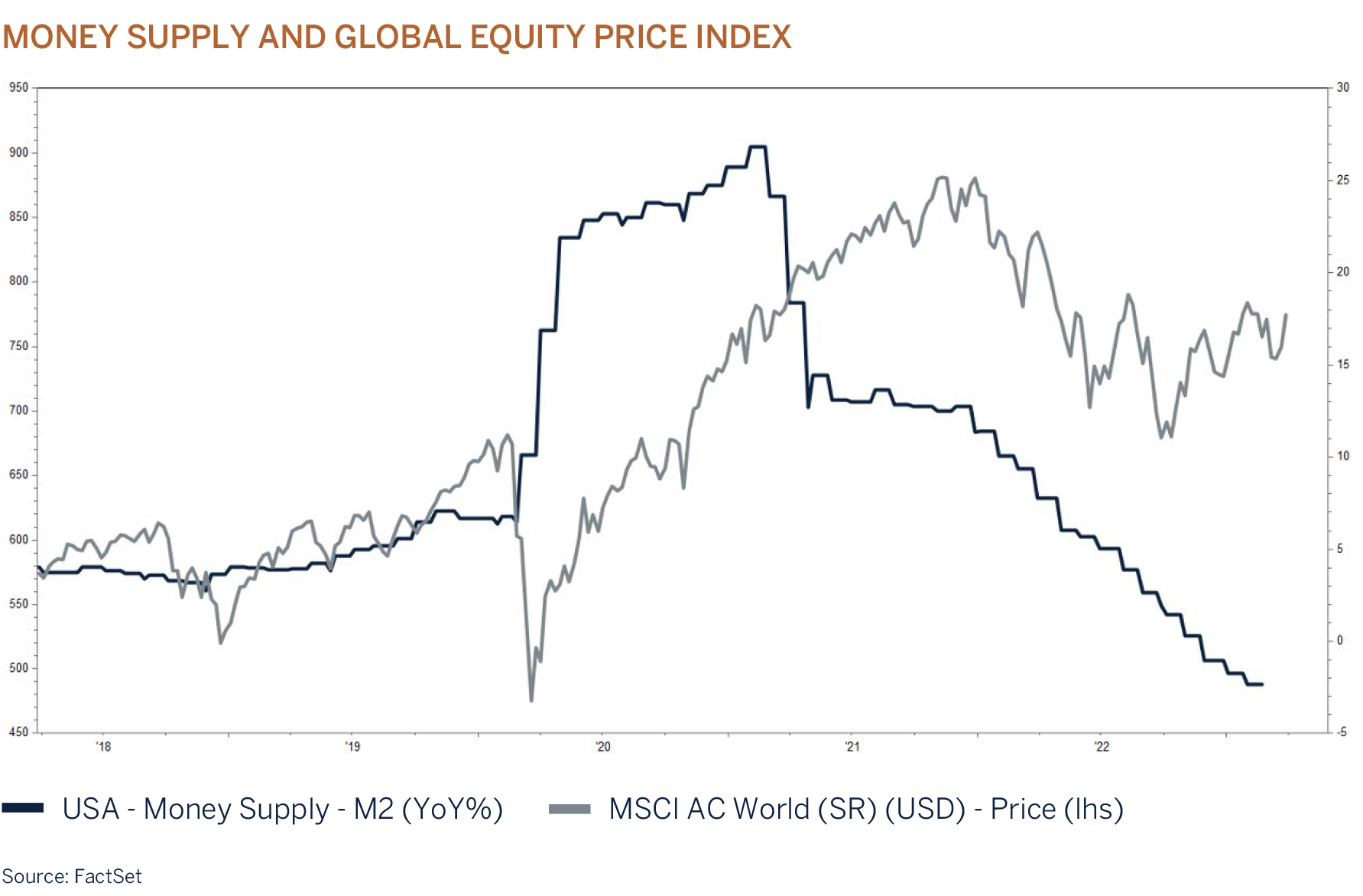

Nevertheless, the lagged effects from higher interest rates have started to take their toll across various sectors in the economy. In particular, the housing market is experiencing widespread weakness as credit conditions tighten and affordability naturally slows. The sector is recalibrating after two years of abnormally strong growth which has resulted in companies rightsizing their workforce. Simultaneously, money supply as measured by M2 (notes and coins in circulation) has turned negative in the US and UK as authorities have been draining excess liquidity from the marketplace in their effort to contain inflationary pressures by inducing weaker demand.

The turmoil in the US and European banking sector is another good example of what can happen when easy money dries up. It was interesting that so much of the focus during the turmoil was centred around the regional banks’ poor liquidity, solvency and risk management, when in fact the main cause was an increasing need for liquidity from their depositors. These depositors were predominantly crypto currency investors, venture capitalists and technology companies (concentration risk). When interest rates were low and money cheap, access to funding by these companies was plentiful and allowed these businesses to invest in growth opportunities or “the next best thing”. Money, from cash flush investors literally poured into these growth businesses. But higher interest rates have made these same investors less willing to commit new capital as the environment became more uncertain and money more expensive. As access to funding became more of a challenge the banks’ clients were forced to draw on their deposits to fund daily operating expenses, which in the end forced the banks to dispose of their assets (predominantly government bonds and asset backed securities) to meet the increase in withdrawals from their depositing clients. Although much of the pain was self-inflicted, this episode is a timely reminder of what can happen when liquidity is withdrawn from financial and credit markets. Despite this, it is not all negative, as the large incumbent banks with strong balance sheets are currently benefitting from the demise of the smaller banks, given the move of deposits from small to large, and what is perceived “safe” banks – it pays to invest in quality.

More disruptive financial market developments are likely the longer interest rates stay at elevated levels. Large companies are perhaps more insulated given that most of their debt is fixed, but many households and smaller companies as well as the struggling commercial real estate sector do not have the same luxury and will be experiencing the pain from higher interest rates as debt facilities come up for renewal at a time when access to credit is getting more difficult and lending standards tighten.

Developments in the labour market

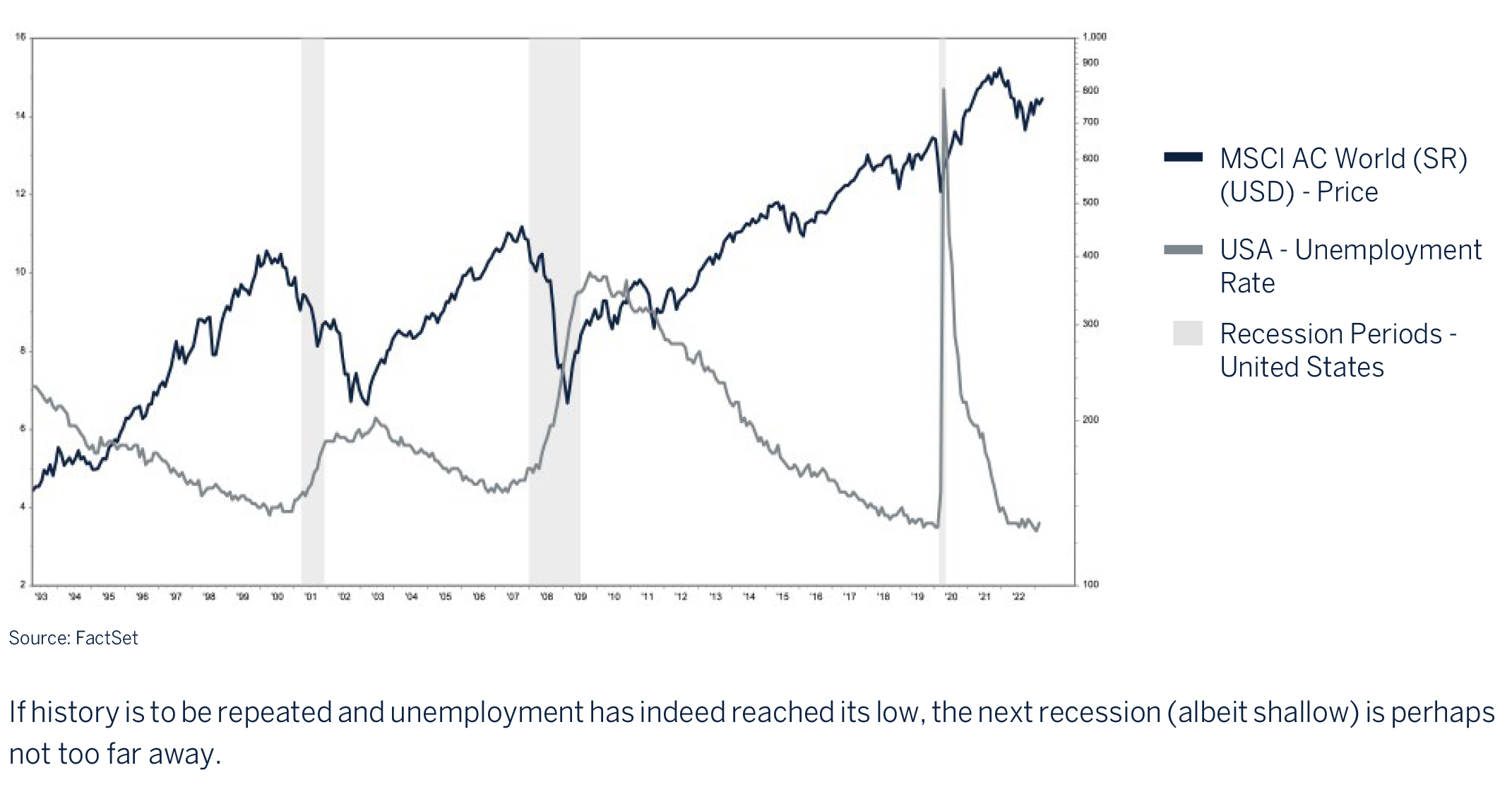

Unemployment across developed markets is at historical lows and has been an important driver, in addition to excess savings, behind the continued strength in consumer spending during a period where extraordinarily high levels of inflation would have normally eaten into households real disposable income. The labour market appears to be robust, with job vacancies plentiful. Unfortunately, the labour market has in the past not been a good signal for what is to come. The strength in the labour market has arguably reached its peak and signals that the global economy might have already reached a late cycle in its expansion phase with a rising likelihood of a recession towards the end of the year and/or beginning of 2024. Historically, the amount of time that passes between the lowest unemployment rate in the cycle, and the next recession is quite short. Although businesses are currently unlikely to retrench, the mix of high rates, tighter credit and profit margin compression should gradually impair their health and profitability, which increases the risk of a slowdown in the labour market in the not-too-distant future.

Conclusion

Although favourable developments in Europe and China are welcome, and indeed should be viewed as very supportive to the economic ‘soft landing’ rhetoric, we still feel that it is too early to call such an outcome. The lagging effect of higher interest rates has yet to play out, whilst better than expected demand from Europe and China will likely lead to inflation being elevated for longer, thereby requiring central banks to keep interest rates higher for a lengthier period than currently predicted. In the very short term, the ‘soft landing’ narrative is likely to support financial assets, but further out risks very much remain. Corporates, investors and households need to go through the process of adapting to an environment of higher for longer interest rates, inflationary costs and a rise in unemployment, all of which looks set to dampen end demand and consumer confidence and result in lower economic activity and corporate earnings.

Investment performance

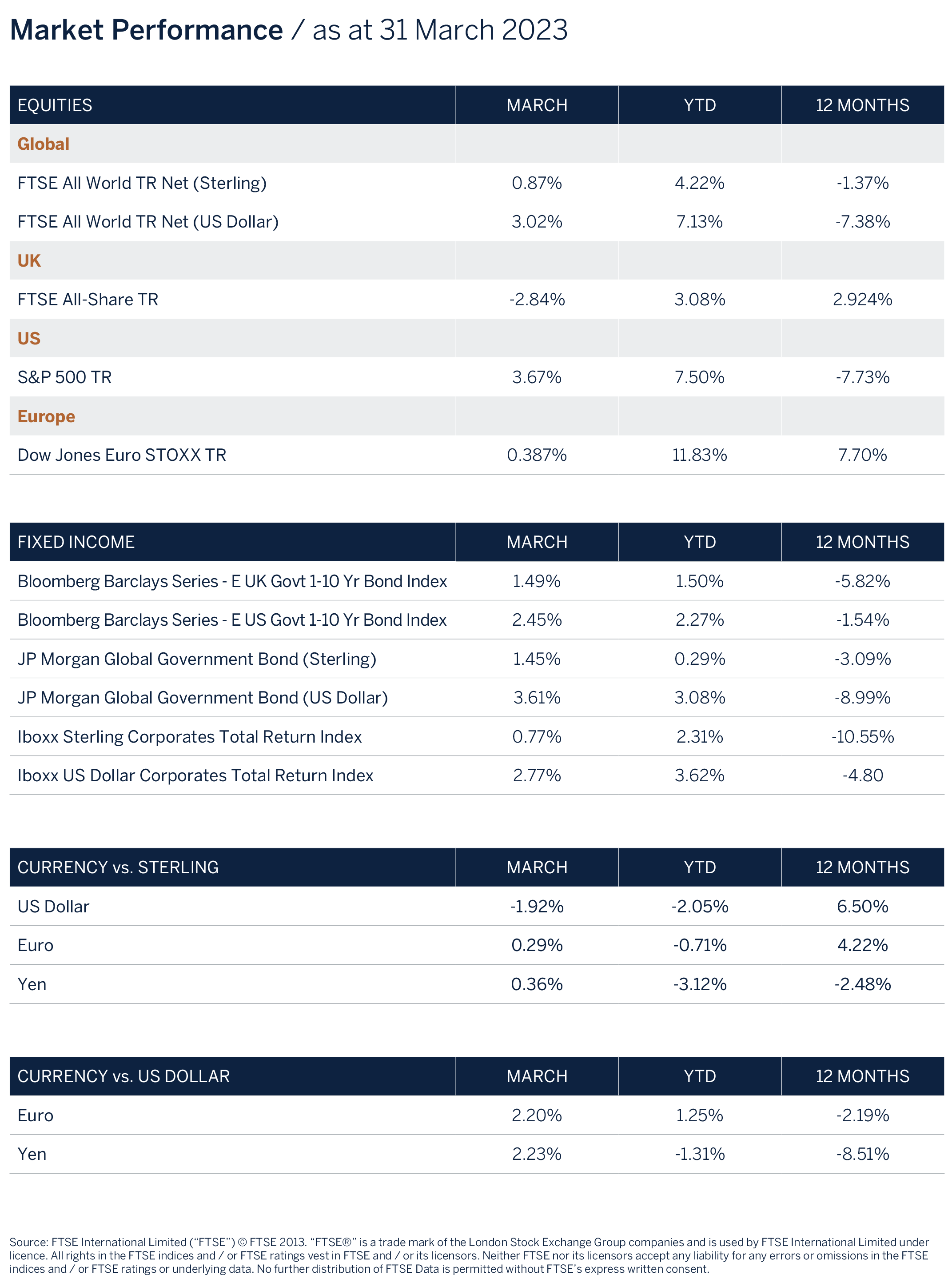

Our tactical underweight equity allocation has been a slight headwind during the volatile 1st quarter. However, following last year’s sharp sell-off and underperformance of quality growth stocks, as expected, the effects of tighter monetary policy and the resultant economic slow-down has led investors to start rotating back to the world’s largest and best managed global companies which look set to emerge in an even stronger competitive position when the current disruptions abate as they wrestle market share from poorly managed competitors. These quality businesses have well-run balance sheets, pricing power, competitive advantages and attractive future growth projections and are used to populate the equity weighting in client portfolios. Some of the best-performing sectors this year, including information technology and communication services were the worst last year. Whilst the energy and commodity sectors, where our investment philosophy and process lead us to be structurally and permanently underweight, have been the poorest performing this year after being standout performers during 2022, as such our quality growth style and stock selection has added value in the period under review and we expect this to continue in the year ahead. Pleasingly, fixed income portfolios and weightings in multi-asset portfolios also delivered positive absolute returns and were broadly in-line with benchmarks.

Asset Classes

| Equities | Underweight |

| Fixed Income | Neutral |

| Cash Plus | Overweight |

We continue to actively monitor the key drivers of asset class returns, which include valuations, the outlook for inflation and interest rates, the change in the direction of leading economic indicators and developments in employment. We stand ready to change tack as the environment dictates and although we believe investors should look forward to a year of improved investment returns in response to lower starting valuations, declining inflation, a peaking interest rate cycle and defensive positioning by market participants, for now, we remain underweight to equities, neutral to fixed income and overweight cash plus.

Global Equity – Underweight

| Consumer Discretionary | Overweight |

| Consumer Staples | Neutral |

| Energy | Underweight |

| Financials | Neutral |

| Healthcare | Overweight |

| Industrials | Neutral |

| Information Technology | Neutral |

| Materials | Neutral |

| Communications Services | Overweight |

| Utilities | Neutral |

| Real Estate | Underweight |

Hoarding of labour likely to dampen corporate profit margins

After the strong, albeit volatile rally in global equity markets since the beginning of this year, on the back of China’s reopening and an improved outlook for Europe given much lower energy prices, valuations for equities, in aggregate (MSCI ACWI), are no longer attractive relative to cash and bonds on a risk adjusted basis. Our one year expected top-down return for the asset class is in line with the other (risk free) asset classes, assuming a positive outcome from earnings growth in 2023, which we believe is unlikely to materialise. Top line corporate earnings growth is expected to decelerate as monetary policy tightens (lower volume growth) and the inflation rate falls.

Furthermore, and given the high job vacancy rate in many economies, employers will be less inclined to cut their workforce, which could result in margin squeeze. The combination of these two factors is likely to result in lower earnings over the next 12 months and will be a headwind for the asset class. Valuations for risk assets, including equities, credit and EM currencies appear to have run ahead of fundamentals in the very short term, and at current prices offer lower margins of safety.

It should be noted however that some of the leading economic indicators appear to have bottomed, and this is something that we will be monitoring closely for signs of an economic recovery. The job market has also remained robust and does provide an underpin to consumer spending. The question remains however – can this trend persist?

Fixed Income – Neutral

| G7 Government | Underweight |

| Investment Grade - Supranational | Overweight |

| Investment Grade - Corporate | Neutral |

| High Yield | Overweight |

Whilst most of 2022 was dominated by sharply rising government bond yields, the quarter under review was characterised by high levels of two-way volatility. The Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond Index, a broad index that tracks the performance of global investment grade bonds, experienced its best January (gaining +3.3%) and worst February (losing -3.3%) since the inception of the index in 1990. This volatility continued in March with sovereign bond yields falling violently as the demise of three US regional banks and the forced takeover of troubled Swiss bank, Credit Suisse by UBS ignited contagion fears in the banking sector and triggered a swift ‘risk off’ episode. The added advantage of a ‘flight to quality’ is that now quality fixed income assets are offering an attractive yield – a proposition that had been absent for many years.

March 16th represented the one-year anniversary since the Federal Reserve (Fed) embarked on one of the fastest rate tightening cycles since the early 1980s. Rampant inflation and the error of ‘being behind the curve’ have forced the Fed to sanction a total of 475 basis points of tightening, lifting the Fed Funds rate to levels not seen since 2007. Whilst the pace of hikes has slowed and, arguably, the central bank has reined in its extreme hawkishness, Fed Chair Jerome Powell has made it clear that the fight against inflation remains the top priority. The Fed is at a difficult juncture, whilst inflation is still excessively high and the economic backdrop remains solid, supported by a robust labour market and a strong services sector, the lagged effects of aggressive monetary tightening are now exposing cracks in pockets of the financial system.

In March, US government two-year yields suffered one of their steepest declines since the crash of 1987, with markets aggressively re-pricing the outlook for interest rates and now expecting rate cuts before year-end. This is firmly at odds with the Fed who have communicated that they do not anticipate cutting rates in 2023. We are cognisant that the recent ‘risk off’ period has tightened financial conditions, and this alleviates the pressure on central banks to an extent, but the recent slide in yields and interest rate expectations has, we believe, been too aggressive given resilient economic growth and inflation well in excess of target levels.

The Bank of England (BOE) sanctioned a further 25 basis point hike in March, taking base rates to 4.25%. The prospect of another hike in May is very much in play following the release of February’s inflation report, which confirmed that the headline rate unexpectedly rose for the first time in four months to 10.4% (annualised). The increase was centred around the services sector, with food and drink prices rising at their fastest pace in 45 years. Services inflation is closely monitored by the BOE as an indicator of wage pressures, which are running at over 6% as many sectors continue to find it difficult to fill vacant positions – this does little to allay concerns that the battle against inflation is anywhere close to being won despite the BOE’s optimistic forecasts. We are cognisant that the UK economy is yet to feel the full effects of a cumulative 415 basis points of monetary tightening, but so far, the consumer has remained resilient enough to keep the economy from slipping into recession.

Over the short-term, we expect yields to surrender some of the recent slide, although a full retracement to the highs of last year is unlikely. It is somewhat ironic that the catalyst (higher interest rates and yields) behind recent volatility is the same one providing an attractive risk-adjusted haven for investors in times of broader market instability. Fundamentally, our view remains that inflation is at, or quickly approaching, a ‘sticky patch’ and economic growth conditions remain resilient (aided by strong employment markets) and in the absence of any additional ‘bank bailout type’ scenarios, yields have little incentive to decline meaningfully from current levels.

At current yields, investors have an opportunity to lockin attractive real (inflation adjusted) yields as inflation normalises over the medium term.

Cash Plus – Overweight

Short term money market instruments are providing attractive yields at present in an environment where the outlook for the global economy and geopolitical environment remains uncertain. These funds will naturally be deployed across the other asset classes when investment opportunities arise.