Quarterly Commentary: Q2 2022

View PDF versionThe times they are a-changin’

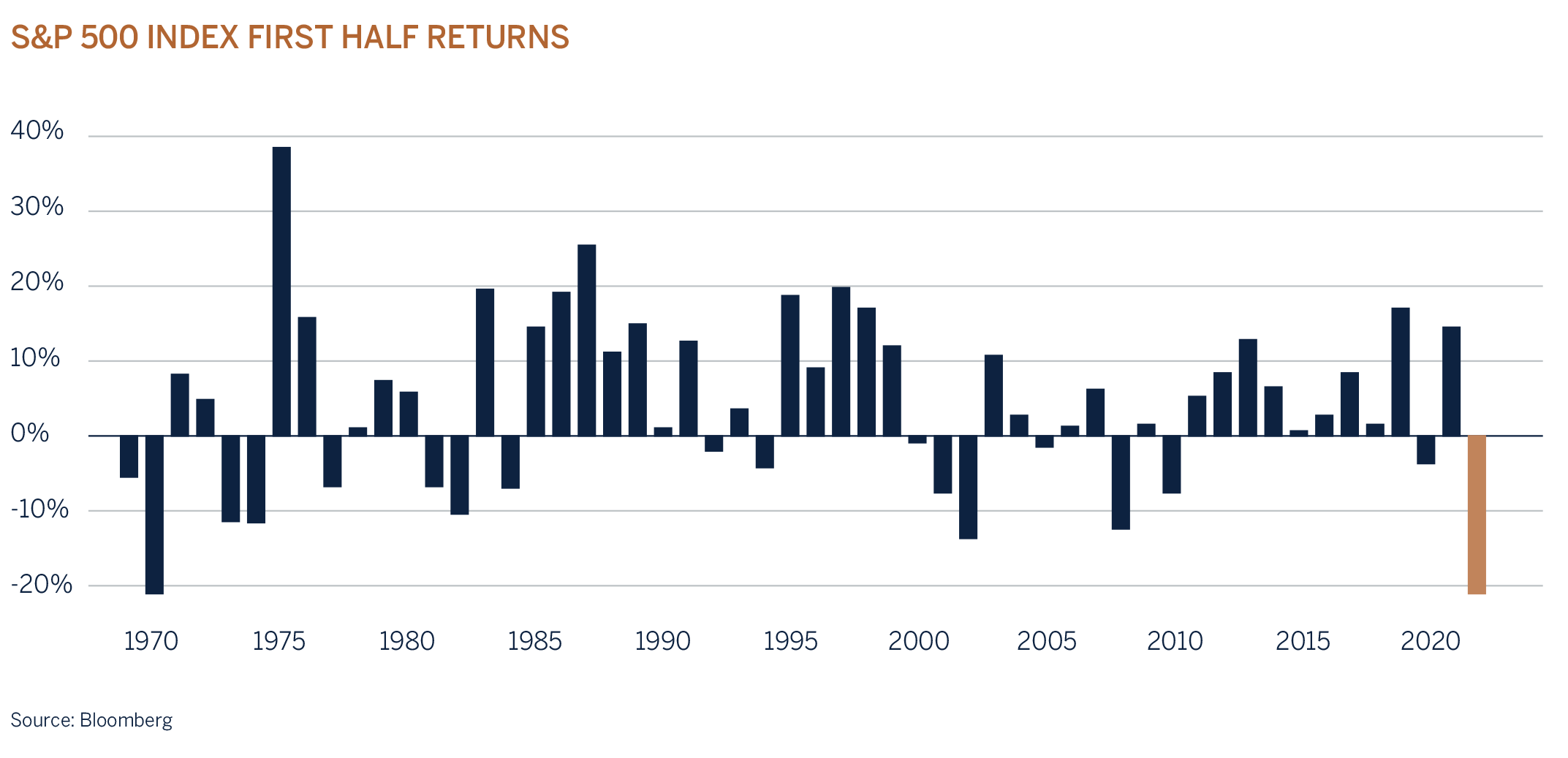

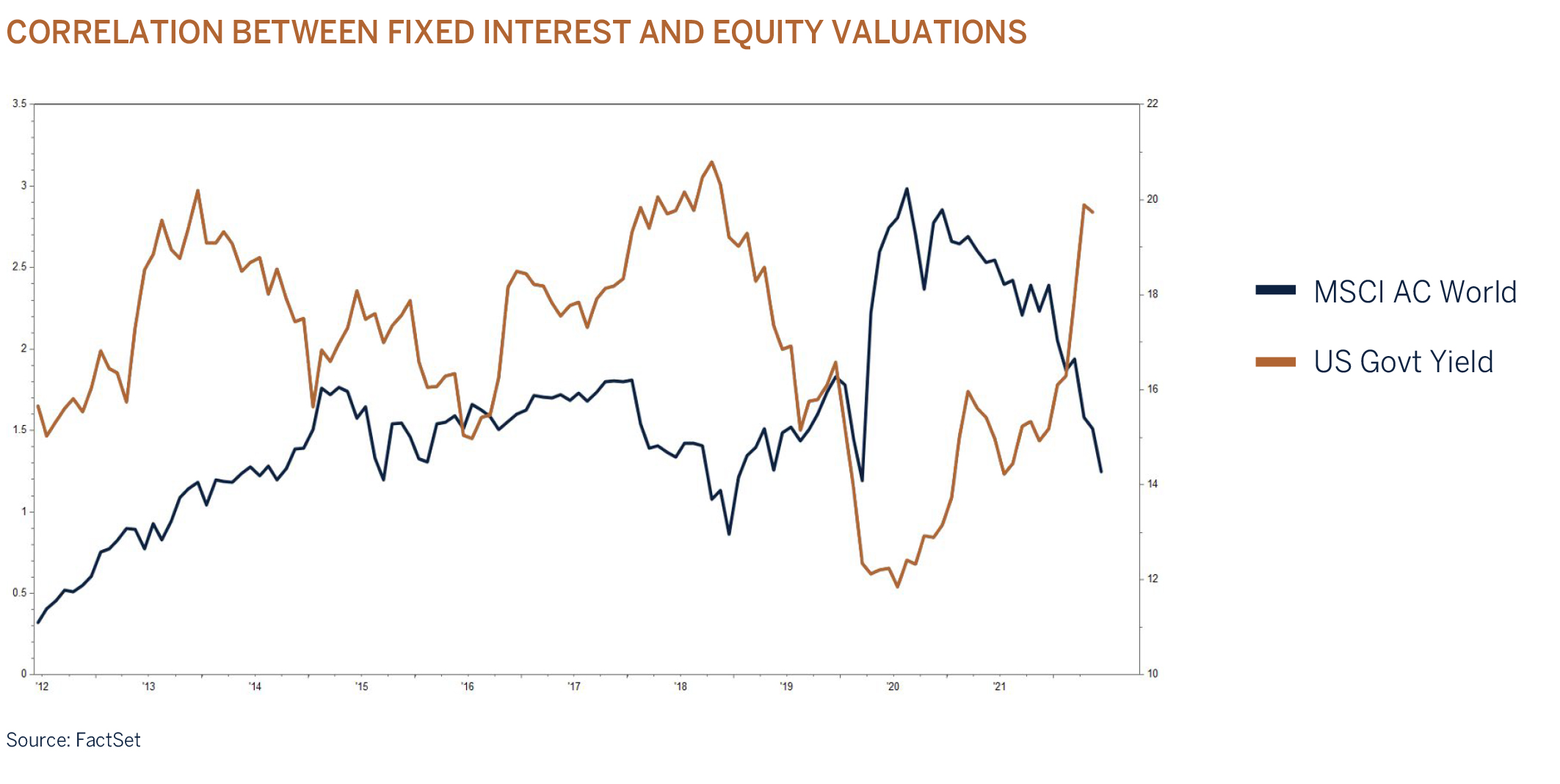

Equity markets experienced their worst start to the year since 1970 as stagflation fears set in and central banks signaled a much firmer stance in bringing inflation under control. Global equity markets have officially entered a bear market after declines of more than 20% from the peak reached in January this year. Defensive stocks have held up reasonably well, but at the end of the first half of the year, the energy sector was the only sector that printed a positive return on the back of materially higher oil prices. Growth stocks in particular (IT and discretionary) came under significant pressure against a background of higher interest rates and elevated valuations. Outside of cash, oil and gold there was nowhere to hide for investors. Global fixed income investors also experienced pain as the capital losses for the year have wiped out nearly 10 years’ worth of income, and investors that chanced their arm at speculative cryptocurrencies will be feeling severely bruised after very sharp sell-offs in their prices. Stagflation is categorised as a period of persistently high inflation and low or stagnant growth, both of which have historically been headwinds to investment markets. Although the sharp increase in inflation, caused by a combination of strong demand and supply disruptions during the pandemic and more recently by the war in Ukraine will ease as commodity prices stabilise, production lines and supply logistics adjust and supply bottlenecks ease, investors have become increasingly concerned about the expected slowdown in economic growth, or even worse the next recession. In our opinion these uncertainties translate into a need for balance in portfolios, and why we think a more neutral allocation to risk assets and government bonds currently makes sense.

Why the sudden reaction?

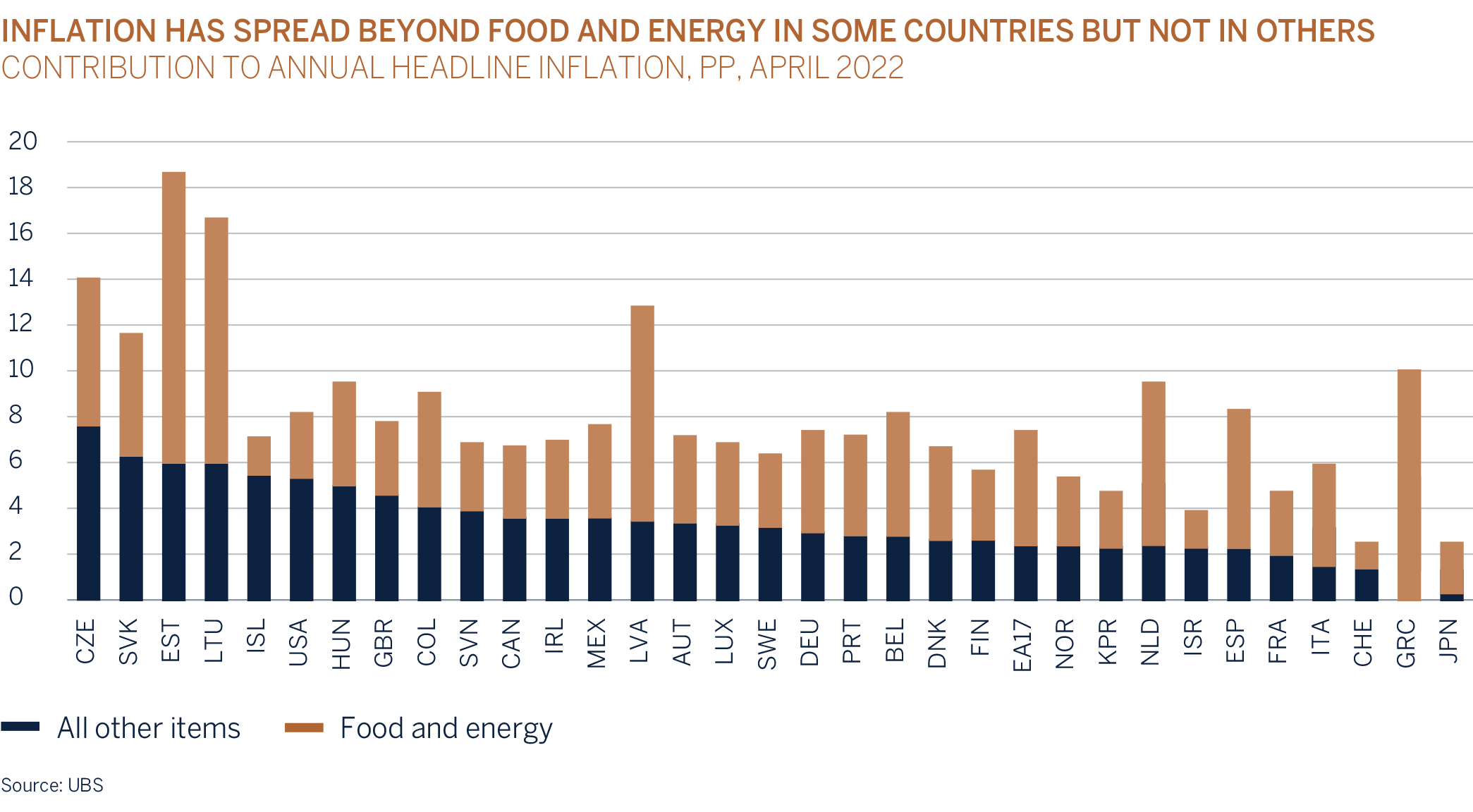

Liquidity, which is the oxygen to economic growth and an important contributor to the performance of risk assets is now no longer expected to be only gradually drained as monetary authorities have become increasingly concerned about the outlook for inflation and are guiding to a period of restrictive monetary policy for the first time in over a decade. Whereas inflation pressures were previously viewed as “transitory”, evidence suggests that inflation is becoming more entrenched and has broadened outside of food and fuel inflation. Inflation levels have become too high for central banks to ignore and, as such, their guidance has become significantly more hawkish over the past few months – central banks are on a mission “to do whatever it takes” to bring inflation under control, and the consequences pose significant risk to the outlook for economic growth.

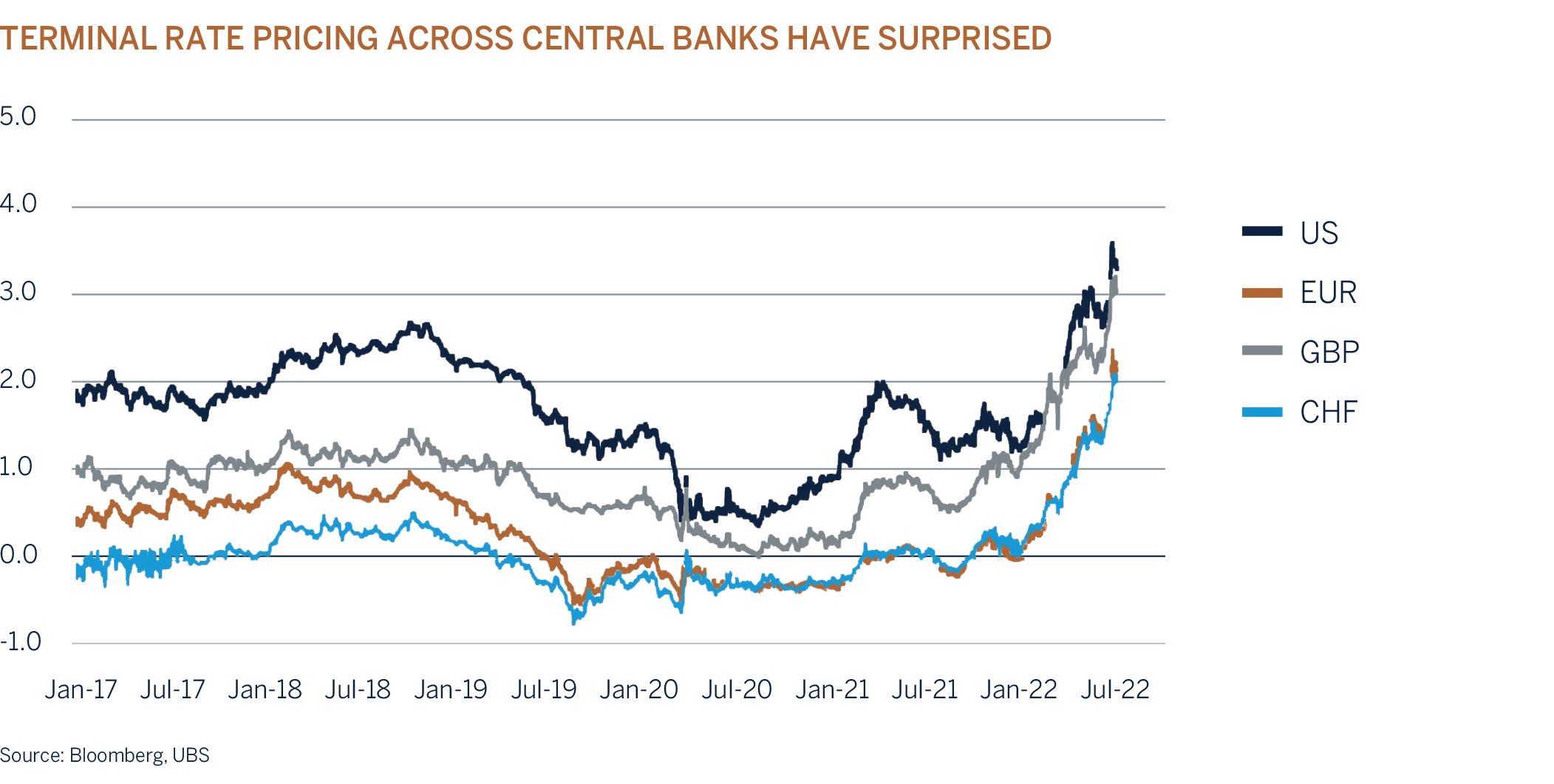

At the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting in June they, like many other central banks, indicated that they are willing to sacrifice near-term economic growth to prevent any lasting price spiral. Demand in developed economies is perceived to be running “too hot” after the unprecedented fiscal and monetary support since the outbreak of COVID-19. Unemployment levels are very low and in the US job vacancies are running at almost double the job seeking rate, driving wages significantly higher, which in turn has been supporting demand and consumer spending. In addition to the 75-basis point interest rate hike announced, the Fed has indicated that interest rates need to increase above its “neutral” rate of 2.5% through-the-cycle to combat inflation by moderating economic activity. The policy rate is now expected to reach 3.5% by the end of this year and to peak at 3.8% next year, before declining again to 3.5% in 2024; i.e. monetary policy is expected to turn restrictive in the next few months. The revised estimates are significantly higher than what was experienced in 2018, when interest rates peaked at 2.5%. Guidance from the Fed at the time was also for interest rates to peak well above the 2.5% level, but the trade war between the US and China had a large enough impact on economic growth, causing the Fed to back off. The key difference however is that inflation has become a much greater concern for central banks to overcome as they strive to defend their credibility.

While the high levels of inflation have been eating into everyone’s disposable income, accumulated savings and strong corporate balance sheets are providing a temporary buffer. Unfortunately, it is the lower income groups and poorer countries that will be most vulnerable to the significant increase in food and fuel prices. Yet it is not only the higher cost of living that will pose a headwind to consumers this year; asset prices have also been trending lower which is resulting in a negative wealth effect and in return lower confidence and willingness to spend on luxury items such as durable goods. Spending patterns have changed this year in favour of experiences (services) such as travelling and eating out. The good news for investors is that product inflation should soon be trending lower as consumers shift their spending away from consuming goods and as supply chain disruptions ease.

While inflation will be trending lower over the next year, the rate of decline remains uncertain, given how buoyant global demand currently is. The duration of the war in Ukraine poses an additional risk to the outlook of many commodity prices. Central banks have realised that they have fallen “behind the curve” and their main concern in the near term is to reduce inflation and, perhaps more importantly, keep inflation expectations under control by draining excess liquidity in the economy through higher interest rates and quantitative tightening (no longer supporting the bond market).

This is a big deal, given that interest rates for both government and corporate bonds have been kept unsustainably low through the bond buying programs by central banks over the past few years, in their effort to provide the necessary liquidity and support to businesses and households affected by the lockdowns during the pandemic. As central banks slowly exit the bond market, fundamentals will once again determine the correct pricing for fixed income securities. Bond investors may demand a higher yield to compensate them for the potential that we have shifted into a new inflation regime, where inflation and interest rates look set to be sustained at higher levels than over the last decade. This adjustment has been costly for bond investors this year, especially those that have been participating in the fixed income market at much lower income yields. It should be noted though that interest rates are already expected to reach levels above 3.5%, meaning a good deal of tightening is already priced into government bonds.

The second order effect of higher interest rates and the impact of the Russia-Ukraine war (supply disruptions, higher fuel and energy costs and higher food prices) is slower growth. The Fed, IMF, World Bank and OECD have lowered their forecasts for economic growth for the next two years, which is now expected to be below trend, with risks firmly tilted to the downside and reflected in moderating leading economic indicators - ex-China where support initiatives from government and the re-opening of the economy after the recent lockdown are expected to underpin growth. The Fed believe that a soft landing (unemployment rate of 4% and inflation at 2%) is achievable, but not a foregone conclusion. There is a lot for investors to digest, which explains the increase in volatility and higher cash holdings in portfolios. Cash holdings across the industry are currently above the levels experienced during the pandemic and will once again provide support to risk assets once inflation and interest rates have peaked. However, this may not be imminent, and investors should expect a bumpy ride until the rhetoric from central banks becomes more balanced.

The change in the outlook for interest rates has come at quite a late stage in the economic cycle. We cannot fault the action by central banks given what’s happened to the inflation trajectory after a period of unprecedented policy support, but it does increase the risks of a policy error which could result in the next recession/economic downturn.

South Africa’s recovery is underway, but headwinds loom

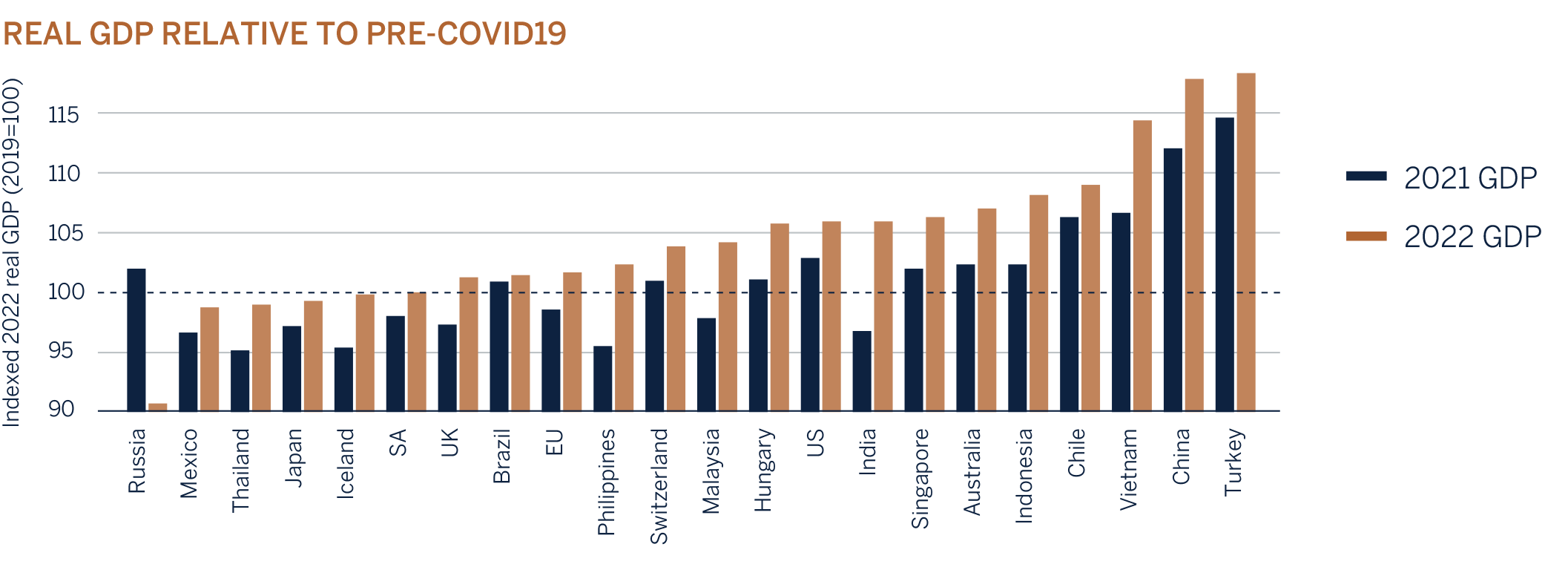

South Africa’s economic recovery from the pandemic has been much slower than many other countries for various reasons, including a sluggish roll out of vaccines, COVID-19 restrictions and the government’s focus on restoring its balance sheet to a more sustainable level after the country’s sovereign debt rating was downgraded to non-investment grade during the midst of the global recession in 2020. In this respect, the first quarter GDP print of 2.1% (quarter on quarter, annualised) was a positive surprise and the economy has now fully recovered back to 2019 levels, driven by growth in Agriculture, Personal Services and Government output. Construction is however still 20% below pre-COVID levels and Mining has unfortunately (again) not been able to fully benefit from high commodity pressures given that production has not yet fully recovered.

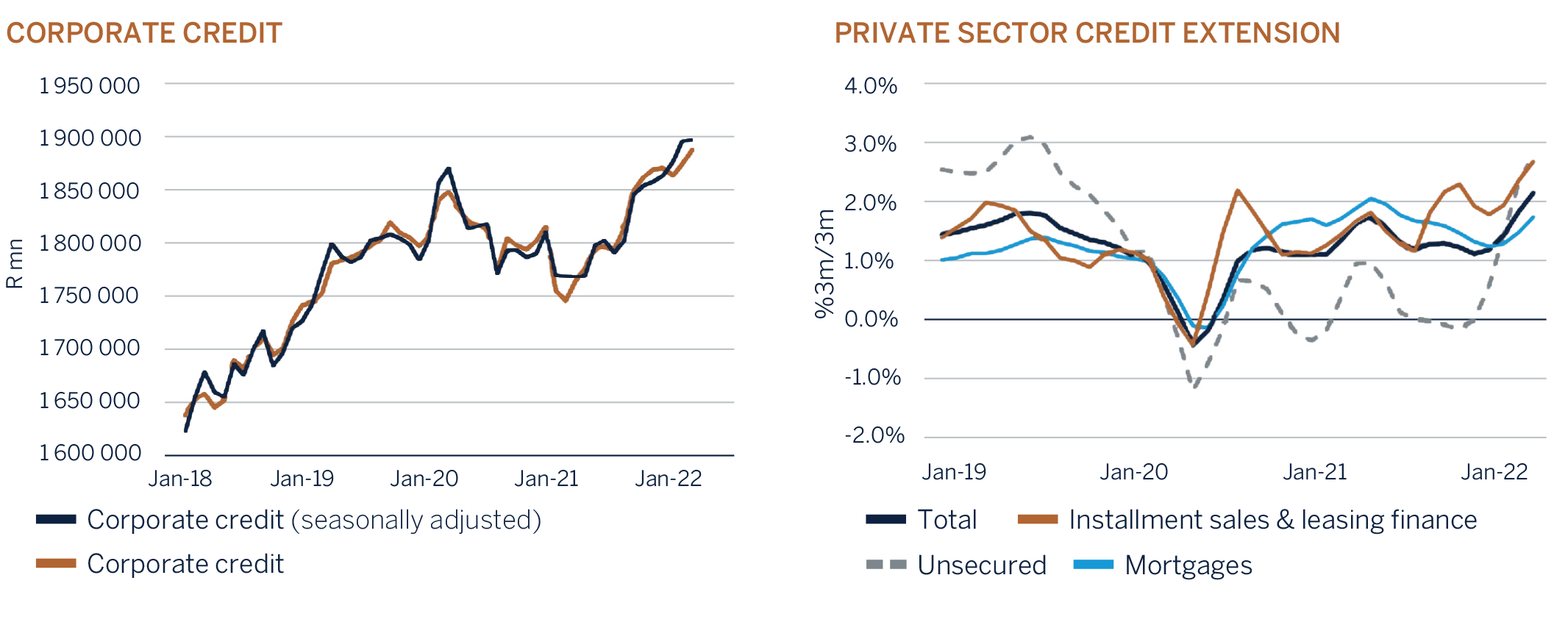

On the expenditure side, it was pleasing to note that Gross Fixed Capital Formation (investment spending) from the private sector as well as Government has picked up strongly after years of underinvesting. Consumer spending has also supported growth with low interest rates, pent up demand and some early signs of improvement in employment (albeit from a low base) and nominal wages driving growth higher. Private Sector Credit Extension has also picked up across the private sector as well as households, a signal that confidence may be improving against a backdrop of low inventory levels and healthy private sector and household balance sheets.

The higher than expected 1Q22 GDP print and signs that Ramaphosa’s structural growth reforms are slowly being implemented have resulted in an increase in growth projections over the next few years to around 2%. Not enough to make a dent in the huge unemployment crisis that the country faces, but certainly enough to provide some hope for many. The improvement in government’s debt profile as a result of the tax revenue bonanza from high commodity prices, record profits from the mining sector and a strong recovery from sectors such as the Banking sector have resulted in positive revisions to SA’s credit rating outlook from both S&P and Moody’s. Government’s commitment to growth reforms and disciplined spending have been cited as positive drivers for an improvement of sustainably higher economic growth in future. Perhaps too early to celebrate, but certainly a step in the right direction.

Unfortunately, quite a lot has changed over the past few months. The outlook for global growth has deteriorated on the back of the war in Ukraine, tighter monetary policy and very high levels of inflation impacting household disposable incomes worldwide. South Africa is not an island and is sure to feel the ripple effect from slower global growth and tightening financial conditions, and once again highlights the importance of successfully implementing structural growth reforms. Not only did the SA economy receive a blow from the devastating floods in KZN, loadshedding is back and with a vengeance. The negative effect on the economy has been declining every year as companies and households have been adjusting and making their own plans to become less reliant on Eskom. But even so, the impact on the economy is negative and reflected in low consumer and business confidence surveys.

Foreign investors will be less inclined to invest in South Africa if basic services, such as electricity generation cannot be relied on. The uncertainty of consistent electricity generation has been one of the main reasons why the mining sector, as an example could not fully benefit from high commodity prices caused by supply constraints and the war in Ukraine. In addition, political uncertainty within the ANC has once again increased as certain factions within the party are looking for any opportunity to get rid of President Ramaphosa. Understandably so, given that corruption and under performance amongst incompetent members of parliament, senior politicians and civil servants are being dealt with more forcefully, with further arrests and a reshuffle likely.

Inflation and a change in the outlook for global interest rates forces the Reserve Bank’s hand

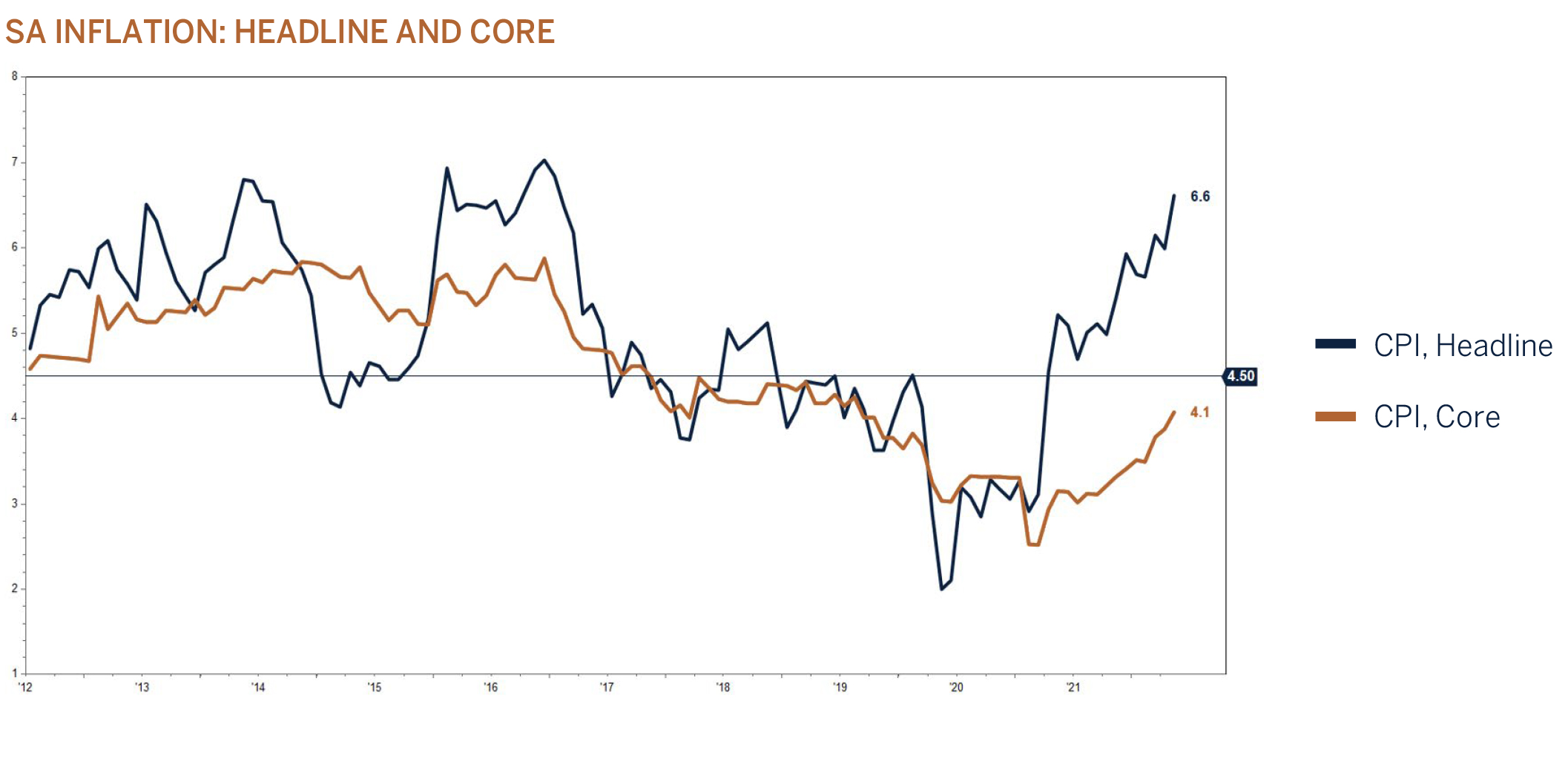

Higher global inflation is starting to filter through the South African economy. Headline inflation of 6.5% is above the Central Bank’s target range of 3-6%, while core inflation has so far been well behaved at 4.1%. The increase in South Africa’s inflation has not been driven by strong demand as has been the case in developed economies, but rather by the same supply disruption factors which have been affecting global inflation and causing the prices of food and fuel to spike simultaneously.

While the Reserve Bank is acutely aware that the drivers of inflation are different to the experience in developed economies and that economic growth in SA remains fragile, its objective is to keep both inflation expectations and near-term inflation within its stated target. This has unfortunately changed with inflation expectations (factored into bond prices) reaching 7% during the month of June. At the same time PPI (cost) inflation has risen to over 10% and perhaps an indication of what is to come from an inflation perspective over the next few months. Base effects on its own will result in lower headline inflation in future. By way of example, even though petrol prices have increased significantly this year, fuel inflation is currently 32.5% against the 40% level reached at the end of December 2021. But the risk is that the increase in headline inflation spills over to core inflation as workers demand higher wages resulting in companies passing on higher costs, and administrative prices (water and electricity) increase to fund the weak balance sheets of SOE’s.

On the back of higher inflation and higher interest rates globally, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) have increased the policy rate at every MPC meeting since December 21. Initially starting with increments of 25bps interest rate hikes and increasing the repo rate by 50bps in May to 4.75%. Given that risks to higher inflation are mounting, the Reserve Bank may well follow the example from Developed Market Central Banks by bringing forward interest rate increases to stave of inflationary pressures sooner rather than later. South Africa’s neutral rate of interest is perceived to be 6.5% or 2% real, and so there is scope for the MPC to increase interest rates to pre-COVID levels of 6.5% before monetary policy becomes too restrictive.

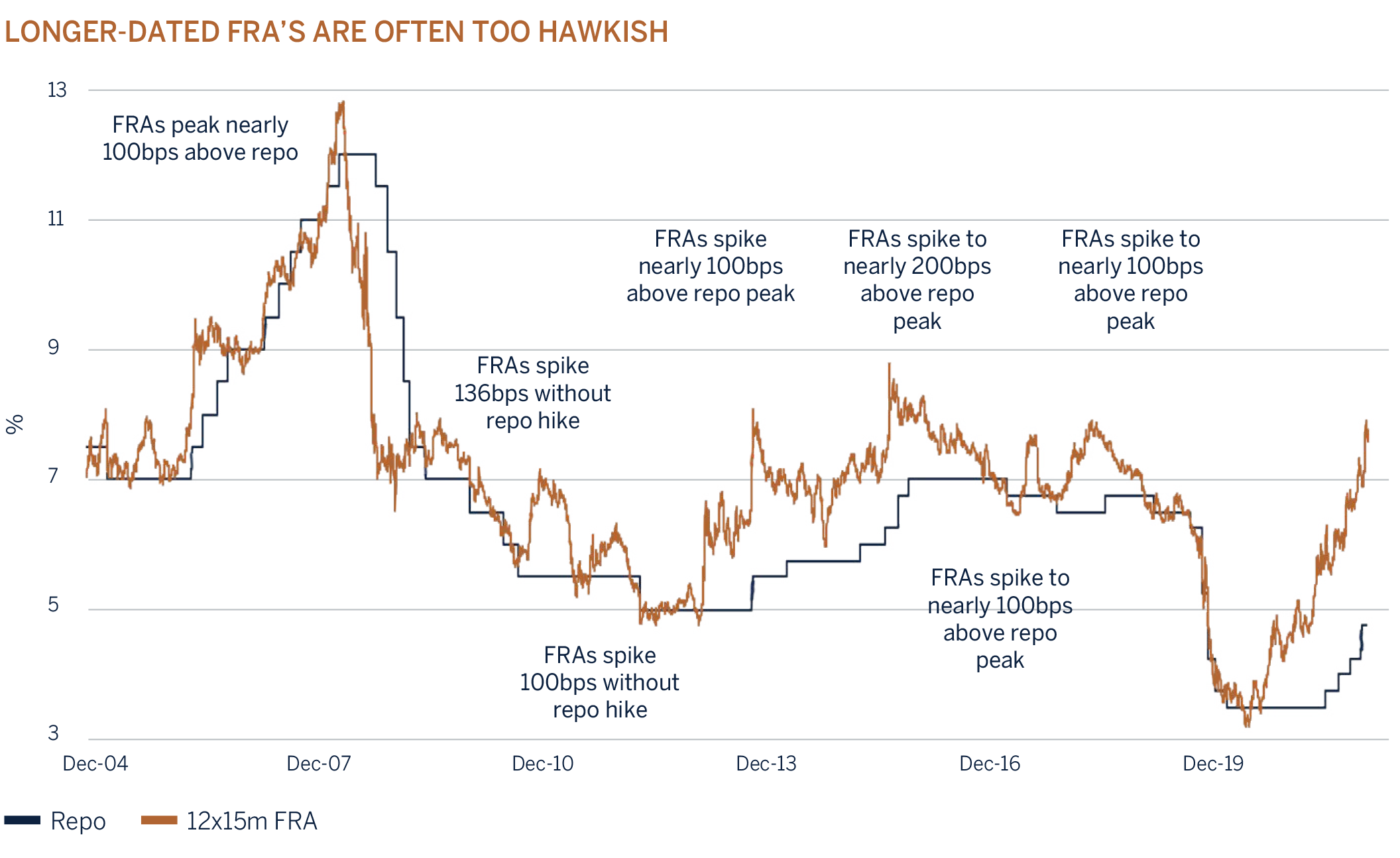

Money Markets (Forward Rate Agreements) have already discounted a significant increase in interest rates (above 7%) over the next year. From the chart below, it is noteworthy that markets have tended to be overly optimistic during periods of monetary tightening and would suggest that interest rates will not reach the current levels of expectations. Irrespective, the combination of higher inflation and interest rates will dampen South Africa’s economic recovery and growth prospects over the short to medium term, with risks tilted to the downside.

SA investment markets follow global markets lower

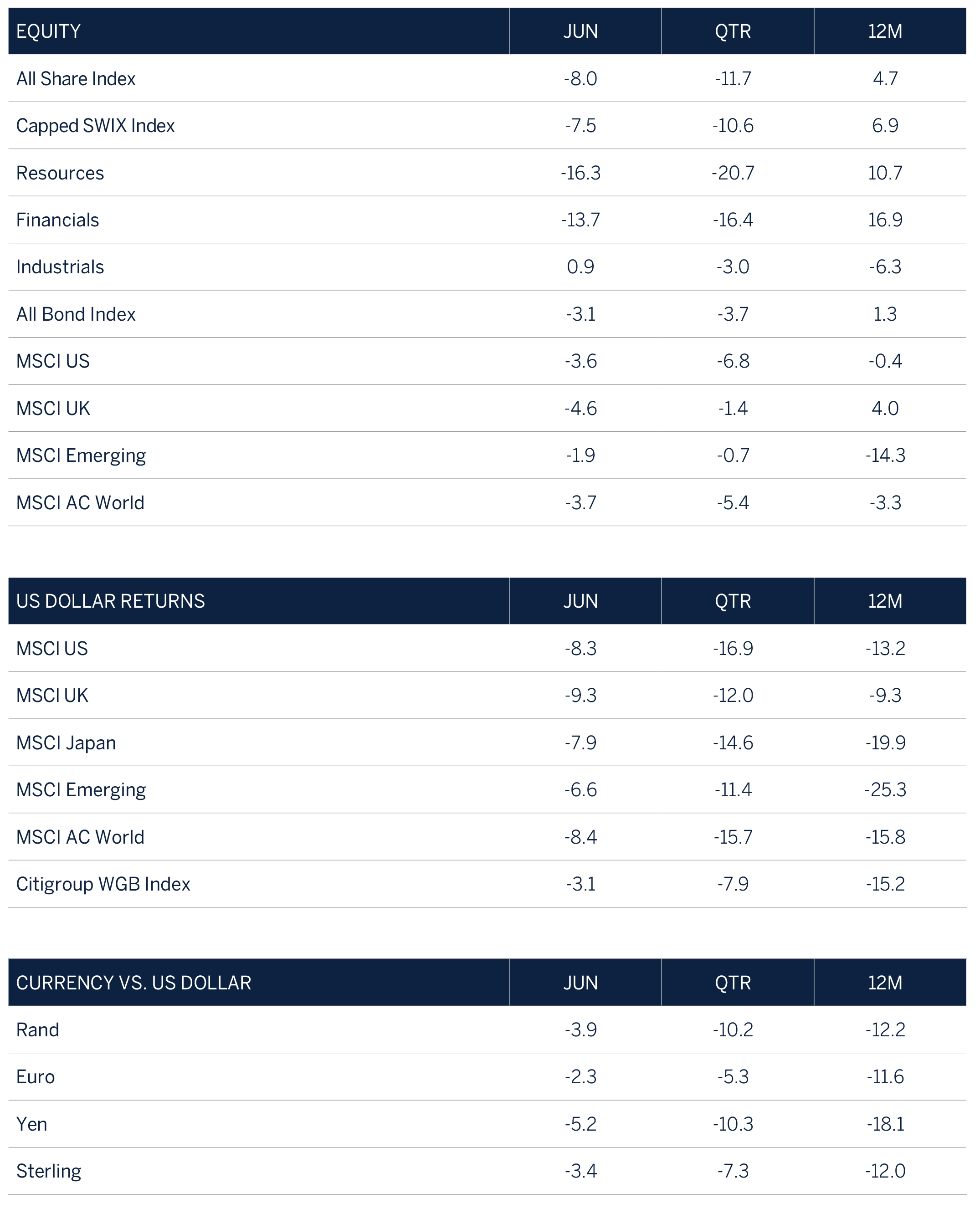

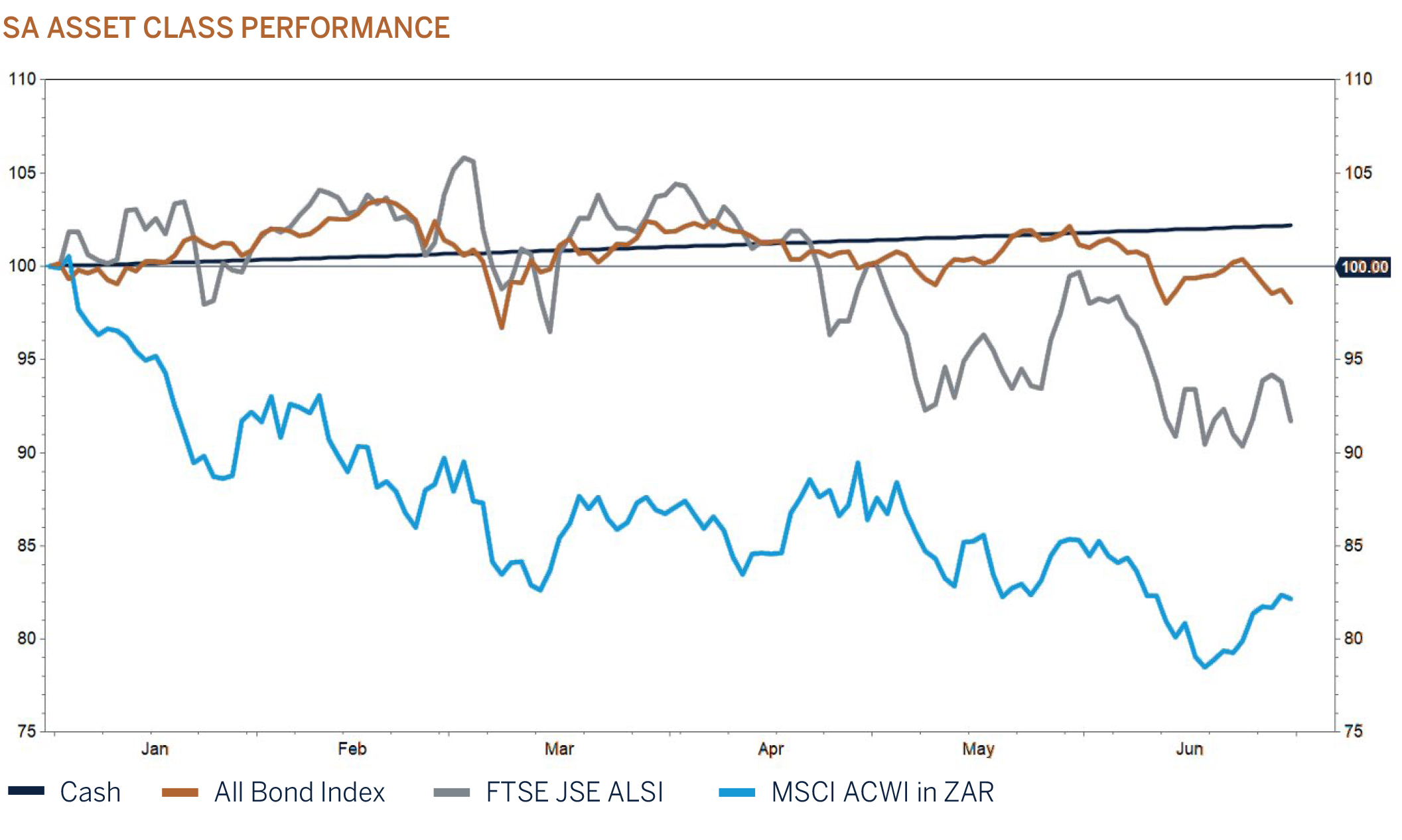

After a good start to the year, SA equities tracked global equity markets lower as the outlook for interest rates and global growth deteriorated. The South African FTSE ALSI Index declined by 11% during the second quarter of the year with Resources and Financials down 21% and 16% respectively. For the calendar year, South African stocks have outperformed their global counterparts by at least 10% given favourable valuation differentials. Even though the sell-off was broad based, the Industrial sector ended the quarter only 3% down on the back of a significant increase in the share prices of Naspers +42% and Prosus +33% during June. An open-ended share buyback program and a commitment to unlocking shareholders value (reducing the discount to Net Asset Value) announced by management propelled the shares higher. South African bonds were not spared and sold off in sympathy with developed market bonds and ended the quarter down 3.7%, with SA’s 10-year government bond at one stage reaching a Yield-to-Maturity of close to 11%, while the Rand depreciated by 10% against a strong USD which benefitted from high interest rates and growth differentials, as well as its status as a safe haven currency during times of uncertainty.

SA ASSET CLASS PERFORMANCE

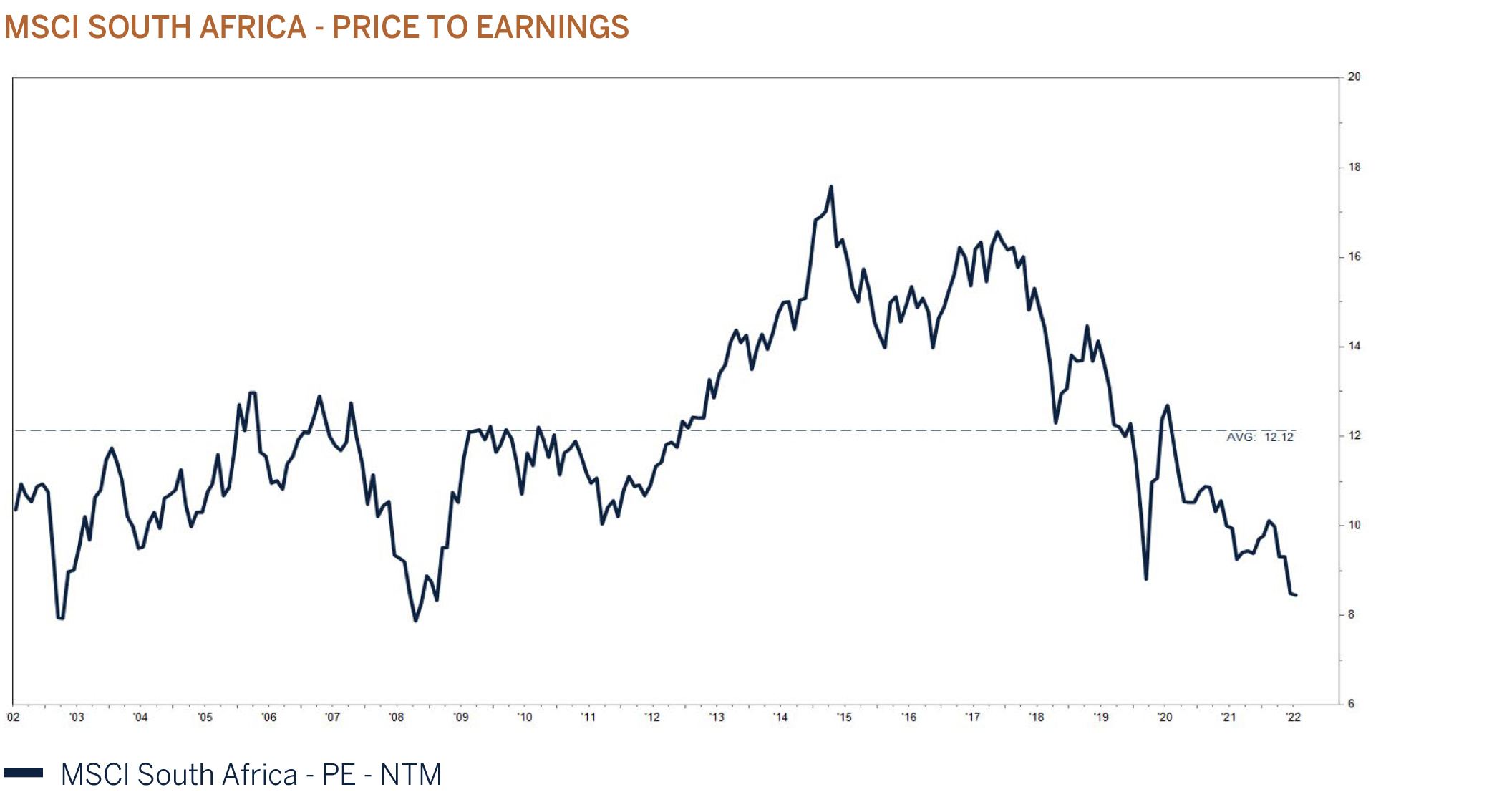

Equity valuations in South Africa have reached depressed levels similar to what was last experienced during the Global Financial Crisis. Current valuations are already below the levels reached in 2020 before central banks and governments stepped in to save the day with unprecedented policy support programs. While risks to the outlook for growth have increased, it is unlikely that earnings will decline at the same magnitude experienced during the Global Financial Crisis, given favourable base effects, and given that many sectors in the economy have not yet fully recovered from the onslaught of the global pandemic - SA’s GDP per capita and investment spending are still well below 2019 levels. Another way to look at it is that for the Price to Earnings ratio to revert to its long term mean, company earnings will have to fall by approximately 40%, or 8% below the levels achieved in 2019. In other words, a lot of bad news is already discounted in valuations, which provides investors with enough margin of safety to navigate through a more uncertain environment in the short term. Sharp corrections and depressed valuations have historically produced strong positive returns over the subsequent 12 months.

Conclusion

Investment markets this year have been taken by surprise by what was supposed to be a gradual tightening in monetary policy. The Fed, ECB and BOE (alongside many other central banks) are on a mission to reduce inflation and inflation expectations. Central banks have signaled that they will continue to hike interest rates until it has become abundantly clear that inflation (and excess demand) is under control. Interest rates are now expected to increase at a rate that we haven’t experienced since 1994 and the impact on economic growth has become increasingly uncertain.

The terminal rate across central banks (peak in expected policy/interest rates) has increased significantly; on average by 200 basis points since the beginning of the year as inflation turned both higher and more entrenched than what was previously expected. It is this sharply higher movement in interest rate expectations that has caused a sudden change in the discount rate used to value the future cash flows of stocks and debt/fixed income instruments. Equity market valuations have adjusted to this new reality and almost all the derating in valuations this year can be explained by higher interest rates rather than a shift in earnings expectations, which has continued to be supportive. The same way that global equity markets and other risk assets benefited from abnormally low interest rates and unprecedented monetary support since March 2020, the opposite has been experienced throughout the course of this year and can continue if inflation expectations do not moderate as expected or if the outlook for earnings growth deteriorates. Many companies, industries and investors have benefitted from a prolonged period of cheap money. This is about to change as an avalanche of tighter monetary policies from central banks around the world are sure to have a rippling effect on growth globally in the coming year.

Our base case is that global economic growth will slow to below trend over the next year, but that a deep and prolonged recession will be avoided given fiscal support, strong household and corporate balance sheets, pent up demand as the world re-opens from COVID restrictions, a buoyant job market and well capitalised financial institutions. In addition, China is expected to support growth as policy restrictions ease after several months of intense Omicron related lockdowns. We are however acutely aware that the environment remains fluid and that forecasting at present is exceptionally difficult given the flurry of potential outcomes. As a result, we remain steadfast in our approach to investing in high quality companies with secular growth profiles, supported by strong balance sheets and to ensure that we don’t overpay for assets. The current environment is sure to provide opportunities for companies with strong pricing power, unique offerings, and wide moats to increase their market share and competitive position as many of the less established unprofitable companies will fall by the wayside as funding becomes more challenging and top line growth starts to slow.

South Africa is sure to feel the effects from slower global growth, high inflation and an increase in interest rates. But, the roll-out of government’s growth initiatives will encourage greater private sector participation in areas such as electricity generation and port and freight management, and should drive investment spending higher over the medium term and provide an underpin to a struggling economy. While there are several hurdles for the country to overcome in the short term, equity and fixed income valuations are cheap by historical standards and provide attractive entry points for patient long term investors that can afford to ride out market fluctuations. We remain comfortable with an overweight position to domestic equity and fixed income.

Asset Allocation

Domestic Equity – Overweight

Domestic equities have held their own through most of this year until the outlook for global inflation, interest rates and growth changed. Since the second quarter, global macro and geopolitical events have overshadowed fundamentals in South Africa with domestic stocks following global stock prices lower. Many domestic companies are currently experiencing a strong recovery in earnings, albeit from a low base. The divergence between share prices that have been weak and earnings growth that has been strongly positive has resulted in valuations becoming even more attractive than when the year started. Current valuations are at depressed levels and will provide a buffer to share prices in the event of a significant slowdown in the global economy. The FTSE JSE All Share Index is trading on a rolling 12-month forward P/E multiple of less than 9 times and a dividend yield of 5%, now in line with periods of extreme uncertainty such as the European Debt Crisis and COVID-19. The rebound in equity returns has historically been very strong from such depressed levels. Every cycle is of course slightly different in its make up, and while global inflation remains stubbornly high and interest rates are trending higher, the underlying value may not be fully realised in the short term. Our approach is to ride out the cycle, instead of trying to “time” the next entry point. Significant upside potential exists for patient investors.

Global Equity – Neutral

Global equity markets have de-rated considerably this year and are trading at levels not too different from their long-term averages with returns expected to be positive for the remainder of the year. Even so, as interest rates increase and with them the discount rate (risk free rate) for long duration growth assets, valuations will remain under pressure and should de-rate further. Sustained high inflation poses an additional headwind to valuations. Earnings growth of 6%-8% over the next year is achievable and will be in line with long term averages, but operating cost pressures do pose a risk for lower profit margins in the future. Strong underlying demand has allowed companies to pass on the costs and maintain gross margins, which has more than offset the increase in operating costs, but this will become more of a challenge for companies to overcome as growth reverts to trend over the next year or two. We are monitoring the effects of the war and sanctions imposed on Russia closely and will reduce risk in portfolios should the medium-term outlook for economic growth and/or expected returns weaken materially and necessitate action.

Domestic Bonds – Overweight

South African bond yields have been following global bond yields higher this year. Given attractive starting yields, domestic bonds have sold off much less than their developed market peers. Government’s debt profile has surprised positively this year as government remained committed to prudent fiscal management and tax revenues have been much stronger than expected. International credit rating agencies have given SA the thumbs up by revising government’s sovereign credit rating outlook higher by one notch. Although it is too early to celebrate, it does signal an improvement in confidence towards SA and perhaps a lower risk premium in future. The domestic fixed income market is not immune to developments in global bond markets but given the attractive starting income yields in both nominal and inflation adjusted terms, we would expect returns to be well above cash over the medium term.

Global Fixed Income - Underweight

Government bond markets have posted deeply negative returns this year, aggressively re-pricing for the new ‘inflationary and tighter policy norm’. Many factors will dictate the direction from here but generally, yields spike most in the early phase of a tightening cycle and that currently seems to be the playbook. However, we still expect yields to climb higher, albeit at a more modest pace, whilst central banks remain firmly in hawkish mode. Our defensive duration strategy has shielded portfolios from the worst of the drawdown in bond markets and although negative returns have been unavoidable, our strategies continue to deliver meaningful outperformance versus benchmarks. While we acknowledge that bond yields could continue to climb higher albeit at a more modest pace, an expected slowdown in the global economy coupled with a peak in inflation will once again be supportive for bonds. We might already be close to such an inflection point and have used this year’s sharp sell-off which has resulted in higher yields as an opportunity to increase client’s exposure to fixed income securities in portfolios, while remaining underweight.

Cash - Underweight

Domestic Equity

|

Basic Materials |

Underweight |

|

Industrials |

Overweight |

|

Consumer Staples |

Overweight |

|

Healthcare |

Overweight |

|

Consumer Discretionary |

Underweight |

|

Telecommunication |

Overweight |

|

Technology |

Overweight |

|

Financial Services |

Underweight |

South African equity declined 10.6% in the second quarter of 2022, as measured by the FTSE / JSE Capped SWIX Index. The second quarter was very volatile. Inflation was the real focal point during the quarter as commodity driven effects from the war in the Ukraine put pressure on central banks around the world as well as a resurgence of global supply disruptions from the shutdowns in China under the Covid zero policy.

The second quarter of 2022 was characterised by central banks around the world being forced to withdraw liquidity and tighten monetary policy as inflation, both current and expected pushed out on the back of renewed supply disruptions and strong energy prices. As such, interest rates rising faster than anticipated first sparked distant memories of stagflation in the 1970’s. In addition, as inflation remained very sticky, fears rocked both equity and bond markets as markets viewed central banks, and the Fed by extension would not be able to manufacture a soft landing this time around and a recession is now a distinct and real possibility in the US and the rest of the world.

As global inflation bit, South Africa did not come out unscathed. While South African equity had held up well in 2022, in June we witnessed a large reversal on the fortunes of South African equity. The broad index was down 10% for the month of June on the back of rising inflation and rising interest rates which will have a severe impact on the fragile consumer. On top of the fragile consumer and diminishing consumption, the power utility Eskom was forced into the worst loadshedding the country has had to endure as the workforce flexed its muscles and embarked on a strike. All these have caused consumer and business confidence to deteriorate, further delaying any potential investment led recovery for the economy.

Consequently, domestic growth in South Africa will remain below the required level to meaningfully reduce unemployment and drive sustainable growth that domestic companies require to generate optimal returns on capital for the foreseeable future. South African equity before the June selloff was trading on valuations that appeared to be attractive in the global context despite the structural economic headwinds. Post the selloff, they appear to be an even better opportunity, despite the tough economic backdrop. This may require a patient investor as equity generally struggles to rerate in a rising interest rate environment but starting to position portfolios to benefit over the long term at current prices looks attractive.

Many of the companies have successfully managed their way through the lockdowns and balance sheets domestically appear to be very healthy. As we move through 2022, the base effects for earnings will become tougher, and earnings delivery will be key. We have a positive outlook on South African equities based on their valuations on an absolute and relative basis.

Domestic Fixed Income

South Africa had a somewhat tumultuous quarter with President Cyril Ramaphosa finally lifting the National State of Disaster in early April, signalling an end in sight to the more onerous COVID-19 related restrictions and restoring hopes of a return to normalcy. The green shoots of optimism were further dampened by the natural disaster which befell KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape to a lesser extent, early in the quarter. Widespread flooding due to inclement weather led to significant losses, some of which are still being tallied. The damage to infrastructure was also considerable, and the provincial government has estimated that infrastructure repair alone will cost about R17 billion. The Port of Durban, which is also a conduit for the import of food, had a backlog of 9000 containers which took more than a week to clear. These supply-chain disruptions likely contributed to exacerbating food cost push factors and spurred inflation higher. This is over and above the cost push factors on oil, commodities and food caused by the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

The conflict in Ukraine continues unabated, with no end in sight. In trying to mediate, several countries including Israel, France and Turkey have stepped into the ring, however, there has been little to no positive result. Consequently, global investors remain riskaverse and asset prices in general sold off sharply during the quarter. The upward trend in South African and global inflation continued and as a result we saw the SARB and other central banks, the US Fed in particular, turning more hawkish and raising interest rates quite aggressively. Business sentiment and leading business cycle indicators were left understandably depressed. The yields on long-term government bonds traded higher (touching 11%) and the currency weakened over the quarter as high inflation, rolling power cuts and higher interest rates had investors fretting over South Africa’s economic outlook.

Green shoots from the infrastructural led economic reforms that President Ramaphosa and his government have embarked on, are beginning to show. Both Moody’s and S&P rating agents revised the country’s credit outlook upwards, with Moody’s from negative to stable whilst S&P revised its outlook to positive. Whilst these developments are positive and encouraging, they do not mask the challenges that remain in stabilising debt and that have been exacerbated by the current economic conditions the country and the rest of the world find themselves in.

Bond yields in South Africa have adjusted to these concerns and are offering good long-term value for investors. It is however very difficult to predict how long the war will last and importantly what its short-term effect on inflation and asset prices will be. In this environment, we expect volatility to persist and believe it is best to be defensively positioned in such circumstances. We will reassess our position as risk unwinds and some level of certainty returns.

Domestic Market Performance % / as at 30 June 2022