The mathematical power of compound growth was scarily apparent earlier this year. Within a matter of weeks COVID-19 cases exponentially multiplied from a few hundred in Asia to infecting millions across the globe.

Compounding often blindsides those with a short-term outlook. Recall the fable about the inventor of chess, who asked his ruler to reward him with a grain of wheat on the first square of the chessboard, two on the next, four on the third, eight on the fourth, and so on. The ruler was pleased to agree to such a seemingly meagre payment. To his surprise his treasury reported the huge number of grains (nine quintillion or 9,223,372,036,854,780,000 to be exact!) on all 64 squares of the board was well beyond the country’s resources. Versions vary as to whether this smart Alec was executed or given the kingdom in lieu of payment.

Unfortunately, there are no 100% per annum investments that will return $9 quintillion after 64 years from an initial $1 outlay. But the snowball effect of returns remains a powerful concept.

This can be illustrated by the rule of 72. This is a method of estimating the numbers of years it takes for your money to double at a given rate of return. You simply divide the rate of return into 72. For example, if the 7% annual average return over the past 30-years on global equities continued to hold then it would take around 10 years to double your money. If you patiently let you nest-egg compound grow for another 10 years you double your money again. Hence, a 7% annual return would turn every $1 into almost $4 over two decades. Caveats apply as these returns are before inflation, taxes or trading costs.

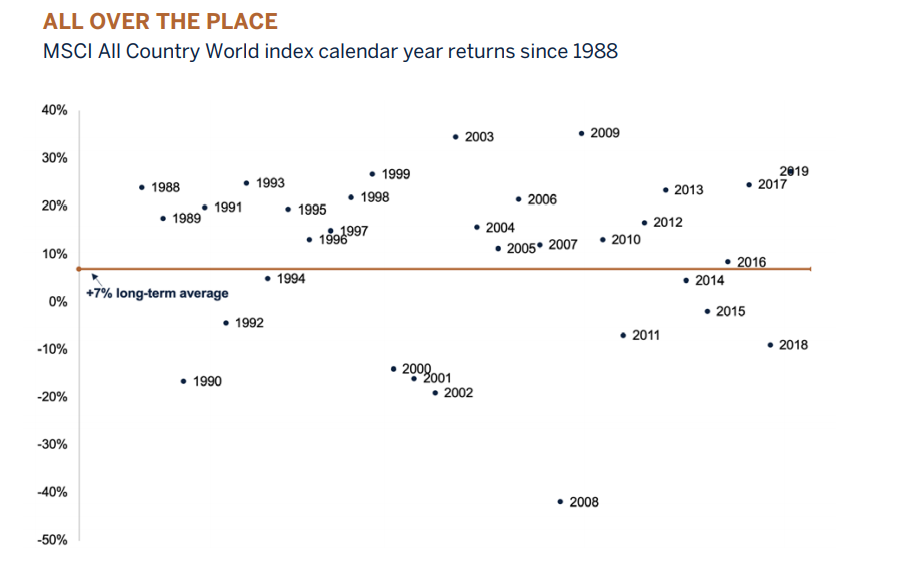

We would strike a note of caution about average returns. They only make sense over the long run. There were only three occasions in the past 30-years where the annual return was close to the 7% long-term average. As shown in the scatter chart, you simply cannot expect to achieve consistent returns over a 12-month time horizon. But you can achieve a near enough result if you are prepared to accept both delightfully and dreadfully performing markets over many years.

To tap into the power of compound returns, Melville Douglas’s game plan is straightforward. It is to invest in value-creating businesses at reasonable prices. Companies are just big machines that use shareholders’ money to invest in products or services with the aim of creating more money through higher profits. If those profits can be recycled back into the business at a similar (or higher) rate of return, then a virtuous cycle is set in place to deliver compound growth. Higher profits make a business more valuable as it provides the capacity to pay larger dividends to its shareholders.

Avoiding big losses is also important. To use a tennis analogy, a long-term track record is more influenced by unforced errors rather than the winners smashed down the line. Trading has a casino-like thrill, but successful investing should be as fun as watching paint dry. If a stock halves in value and then rises 50%, it has still lost 25% of its value. The big short-term wins in risky stocks are often a mirage. Better to dully plod along and compound at a steady pace. The big money is made by those who can stay the course, do the hard yards and (most of all) stick to their investment philosophy.

Albert Einstein described compounding as the “eighth wonder of the world”. One of history’s greatest minds reputedly said, “he who understands it, earns it; he who doesn’t pays it”. Who are we to argue?